Queer for Fear: Bryan Fuller on horror, trauma and dealing with homophobia on American Gods

Bryan Fuller on his love for horror. (Getty)

For Bryan Fuller, who’s known for bringing shows like American Gods and Hannibal to television, it makes perfect sense that Dracula and Frankenstein were both created by queer writers.

Both Mary Shelley and Bram Stoker wrote intimate letters about their same-sex desires during their lifetimes. It’s no surprise that they became famous for writing novels about misunderstood monsters.

As Fuller tells PinkNews: “What was fantastic about early horror literature was that we often went to the monster’s point of view, and that is a point of view that is going to be more relatable to people who are on the fringes of society.”

It’s that idea of the other that underpins Queer for Fear, a five-part documentary series from horror streamer Shudder exploring queer representation in the genre. From Hitchcock to the pansy craze, it shows how horror has provided fertile territory to explore life on the periphery.

Fuller, who serves as executive producer on the series, has been fascinated with the horror genre since he was just a child, and he hasn’t let go of the thrill of being afraid ever since.

“There was a lot of gateway horror that got me into the genre,” Fuller explains. “The Wizard of Oz was a perennial that we saw every year. And then as I got a little bit older – I think I was 10 when I saw The Shining – which was really impactful. I related deeply to a sensitive kid trying to navigate a situation with an abusive father and that felt like something that was queer in and of itself.

Shelley Duvall, Danny Lloyd, and Jack Nicholson in car on their way to resort in The Shining. (Warner Brothers/Getty)

At the core of the horror genre is trauma – most films see protagonists pushed into terrifying circumstances most people couldn’t even begin to imagine. Does Fuller think that’s part of the reason queer people – many of whom also face devastating traumas – find so much in the genre?

“Absolutely,” he says. It’s why The Shining resonated so strongly with him – because he grew up in what he describes as “a violent home”.

“There was something about that that really spoke to me and I perhaps wasn’t completely aware of it.

“But, some therapy later, and some ‘aha’ moments [later], it was like, ‘oh, that’s why I’m connecting to this material, because it’s a sensitive little boy whose father wants to destroy him for being sensitive.’ And that’s kind of a narrative on the queer spectrum.”

Queercoding as a ‘safety’ mechanism

Because queer characters couldn’t be overtly depicted on screen for a long time, queercoding became a prism through which queer creators could reflect life on the periphery. The term refers to characters who read as queer to LGBTQ+ audiences, but whose queerness is never explicitly stated.

Fuller says queercoding was a “safety” mechanism for creator and audience alike – it meant they didn’t have to “expose themselves”.

“As Justin [Simien] says in the documentary, if you know you know and you get something out of it, but you don’t necessarily have to expose yourself just because you’ve exposed the code.”

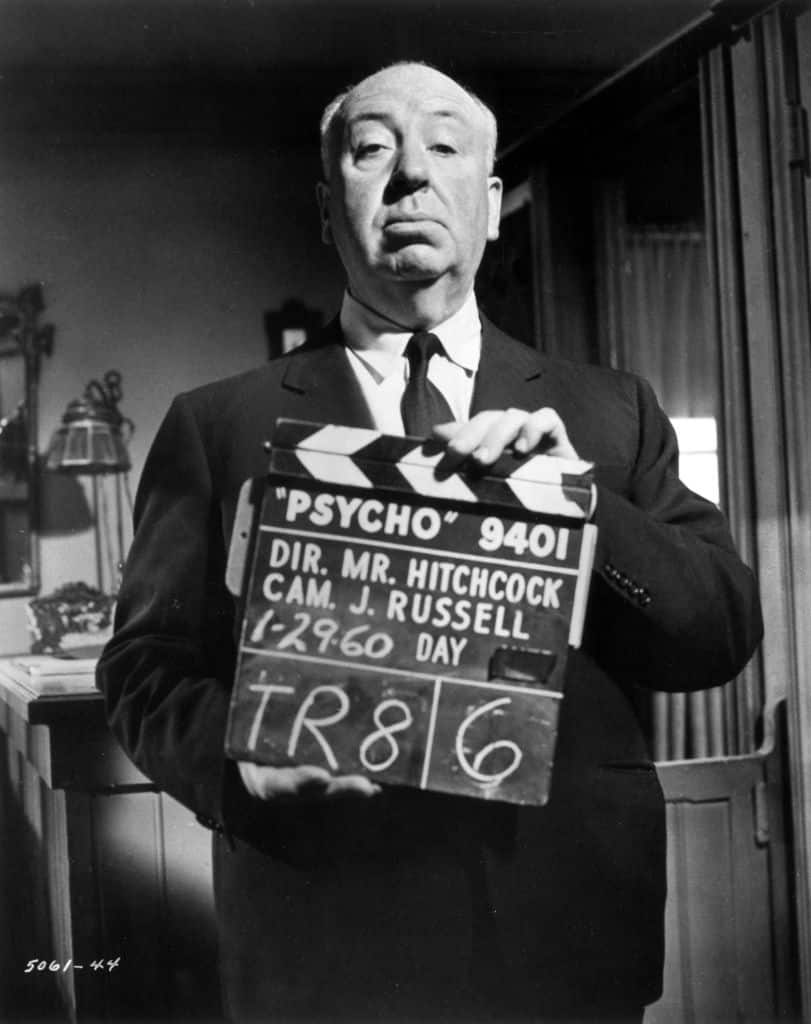

One of the famous horror creators Queer for Fear explores is Alfred Hitchcock, who turned queercoding into an art form of its own in films like Rebecca and North by Northwest. He also famously pathologised cross-dressing in Psycho.

Alfred Hitchcock holding up a clapperboard on the set of Psycho. (Hulton Archive/Getty)

Fuller is surprised Hitchcock doesn’t come up more in conversations about queer horror.

“That was one of my favourite parts and one of the things I was most interested in when I got involved in this project,” Fuller says. “I was like, ‘You have to cover Hitchcock,’ and it was fascinating because everybody said, ‘Why?’ And I was like, ‘Are you kidding me?’ Because it was so obvious to so many folks.”

Fuller explains: “Hitchcock wasn’t traditionally thought of through a queer lens, even though he played heavily with queer ideas and themes. I think because it was so mainstream and so acceptable it became one of those things where straight people were telling queer people, ‘Not everything is about you,’ but in some instances it is.”

Hitchcock was “steeped” in queer culture in the ‘20s and ‘30s in London, Fuller says, which likely fed into his filmmaking career.

There are also questions about how Hitchcock identified – and whether he might have been queer himself.

“When you look at his movies and look at which friends of his he is casting in those movies, you get that this guy is more consistently open to dealing with queer subject matter than any other mainstream filmmaker of that era.

“That’s pretty fascinating, and then you dig a little bit deeper into some of the things he said in personal conversations – about how, if he hadn’t met Alma [Reville, Hitchock’s wife] at the right time he would have turned out to be a poof…”

We saw with Bros, straight people aren’t necessarily going to turn out for a queer narrative.

As time goes by, queercoding becomes less necessary. Today, queer characters crop up in television shows and films all the time.

Could Fuller have imagined how much things would change when he was a queer kid?

“Yeah, because I grew up in the ‘80s and there were certain movies that were trying to tackle this subject matter, whether it’s Partners with Ryan O’Neal and John Hurt or Making Love. There were queer stories out there but they were really arthouse fare or they were depicting queers as villains. I think the big difference will be when it’s a big success.”

Queer projects have become successful on television, but the same isn’t true of the major studio fare that makes its way into cinemas.

“We saw with Bros, straight people aren’t necessarily going to turn out for a queer narrative. It’s happened before and it’s happened again… mainstream success is still going to escape us for a little bit, I think,” Fuller says.

Queer creators still face ‘obstacles’

That’s not to say that things aren’t changing for the better. Fuller has watched from the inside as the industry has gradually shifted away from censoring queer content. He faced “a lot of obstacles” getting anything with explicit queerness made early in his career – that doesn’t happen as much today.

But that doesn’t mean things are perfect either.

There was an actor on the set of American Gods who would tell f*g jokes

“Everything that I’ve done from Dead Like Me to Wonderfalls had queer characters in it and it was a trial to get them on screen,” Fuller says.

“In the case of Dead Like Me the studio made the gay character straight. It was very frustrating. In Wonderfalls we couldn’t allow the two queer women to kiss.

“Along the way I have experienced a lot of studio executives, network regimes, and actors and actors’ managers who have all said, no, queerness is beneath us or not allowed or reprehensible in some way.”

Fuller pinpoints American Gods as the moment he saw things were starting to change – but that didn’t mean the industry became a warm haven for queer people overnight.

Orlando Jones, Omid Abtahi, Mousa Kraish, Bryan Fuller, Yetide Bakadi, Michael Green, Neil Gaiman, Bruce Langley and Chris Obi arrive at the “American Gods” advance screening In Partnership with GLAAD at The Paley Center for Media on May 10, 2017. (Joe Scarnici/Getty)

“It was fascinating with American Gods, we got to have an explicit same-sex romance and a very explicit sex scene, but there was an actor on the set of American Gods who would tell f*g jokes when they were mad at me and they would make sure that I could hear them,” Fuller says.

“The studio, when I brought those complaints to them, did nothing and said that they were going to do nothing. So even though we got representation and we were able to depict it on the screen, there were still homophobes on the set who were saying really nasty s**t and getting away with it and having absolutely no consequences for their homophobia and abusive behaviour.”

Things might be better, but homophobia in Hollywood is alive and well.

“It’s a hard lesson to take away something from… just because one thing might shift on screen because of the public awareness of how we are telling these stories, behind the scenes homophobes are still thriving.”

Queer for Fear is streaming on Shudder now.