The complicated legacy of the Wolfenden Report, which changed the trajectory of UK LGBTQ+ rights

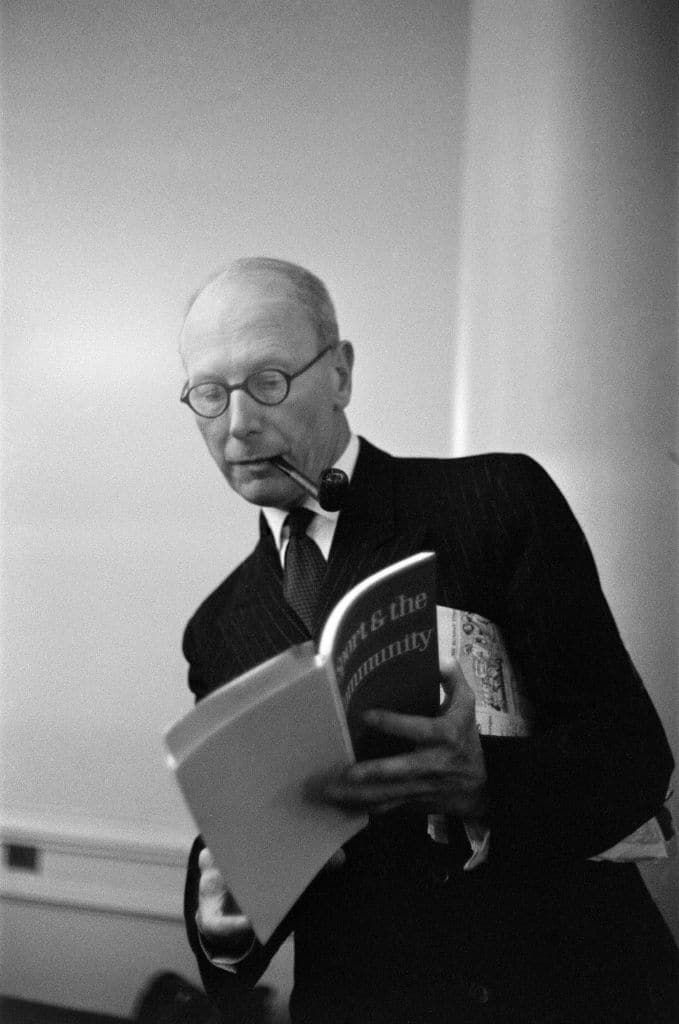

Sir John Wolfenden (right) meets members of the press at the Waldorf Hotel for discussions and questions on the Wolfenden Committee Report on Sport. (Terry Fincher/Mirrorpix/Getty)

On 4 September 1957, the Wolfenden Report, which recommended “homosexual behaviour between consenting adults in private should no longer be considered a criminal offence”, was published.

In some ways, the 155-page report was groundbreaking and paved the way for the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in England and Wales 10 years later.

But the Wolfenden Report only went so far.

Its recommendations were steeped in conservatism, and ensured homosexuality would continue to be a punishable offence in England and Wales for years to come – even if a blanket ban was no longer in place.

Wolfenden Report has a complicated legacy

The history of the criminalisation of homosexuality in England began in 1533 when the Buggery Act was passed during Henry VIII’s reign. Up until 1861, men who were found guilty of homosexuality could be sentenced to death, while others were imprisoned or deported to Australia.

Eventually, the British state moved away from executing homosexuals – but that didn’t mean it was ready to condone same-sex sexual relations. In 1885, the Criminal Law Amendment Act was passed, which only served to strengthen anti-gay laws in the UK.

That law remained in place for decades. In the years after the Second World War, the number of men convicted of homosexual activity began to increase, while a number of high-profile cases thrust the issue into the government’s sights.

In 1954, after Lord Montagu of Beaulieu was convicted of “gross indecency” alongside journalist Peter Wildeblood and Michael Pitt-Rivers, the government decided to set up a committee to examine the issue.

Sir John Wolfenden, who was then vice-chancellor of Reading University, was appointed as chair of the committee.

On 15 September 1954, the Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution in Great Britain met for the first time. It convened 62 times in the years that followed, with some of those sessions used to interview witnesses such as Carl Winter, Patrick Trevor-Roper and Wildeblood.

Three years after their first meeting, the committee issued its report. Ultimately, they found the law’s purpose is to “preserve public order and decency, to protect the citizen from what is offensive or injurious, and to provide sufficient safeguards against exploitation and corruption of others, particularly those who are specially vulnerable”.

The report said: “It is not, in our view, the function of the law to intervene in the private life of citizens, or to seek to enforce any particular pattern of behaviour, further than is necessary to carry out the purposes we have outlined.”

The report failed to win popular support

The Wolfenden report did not go down well in government circles. It failed to win the support of the then home secretary, nor did it win over the House of Lords. Ultimately the government decided to ignore its recommendations, meaning homosexuality would continue to be fully criminalised.

However, the report did succeed in starting a public conversation on the issue. In March 1958, The Times published an article by academic Tony Dyson, who called for the recommendations to be reconsidered by the government. It was co-signed by a number of high-profile figures of the day, including the writer J.B. Priestly, and it brought together some of the people who would go on to form the Homosexual Law Reform Society.

A full decade on, the Sexual Offences Act was passed by parliament – that piece of legislation finally enacted the recommendations made in the Wolfenden report.

Sadly, the Sexual Offences Act, while groundbreaking, did little to change life for gay and bisexual men in England and Wales. It only decriminalised homosexuality in private and where both parties were aged 21 or over, meaning gay and bisexual men would continue to be punished by the state for decades to come.

That root of that failure to implement adequate reform lies in the Wolfenden report.

Wolfenden report recommended ‘very partial law reform’

It should go without saying that, 65 years on, the Wolfenden Report has a polarising history.

While the committee helped move the dial on the discussion surrounding homosexuality, its recommendations did little to change life for gay people.

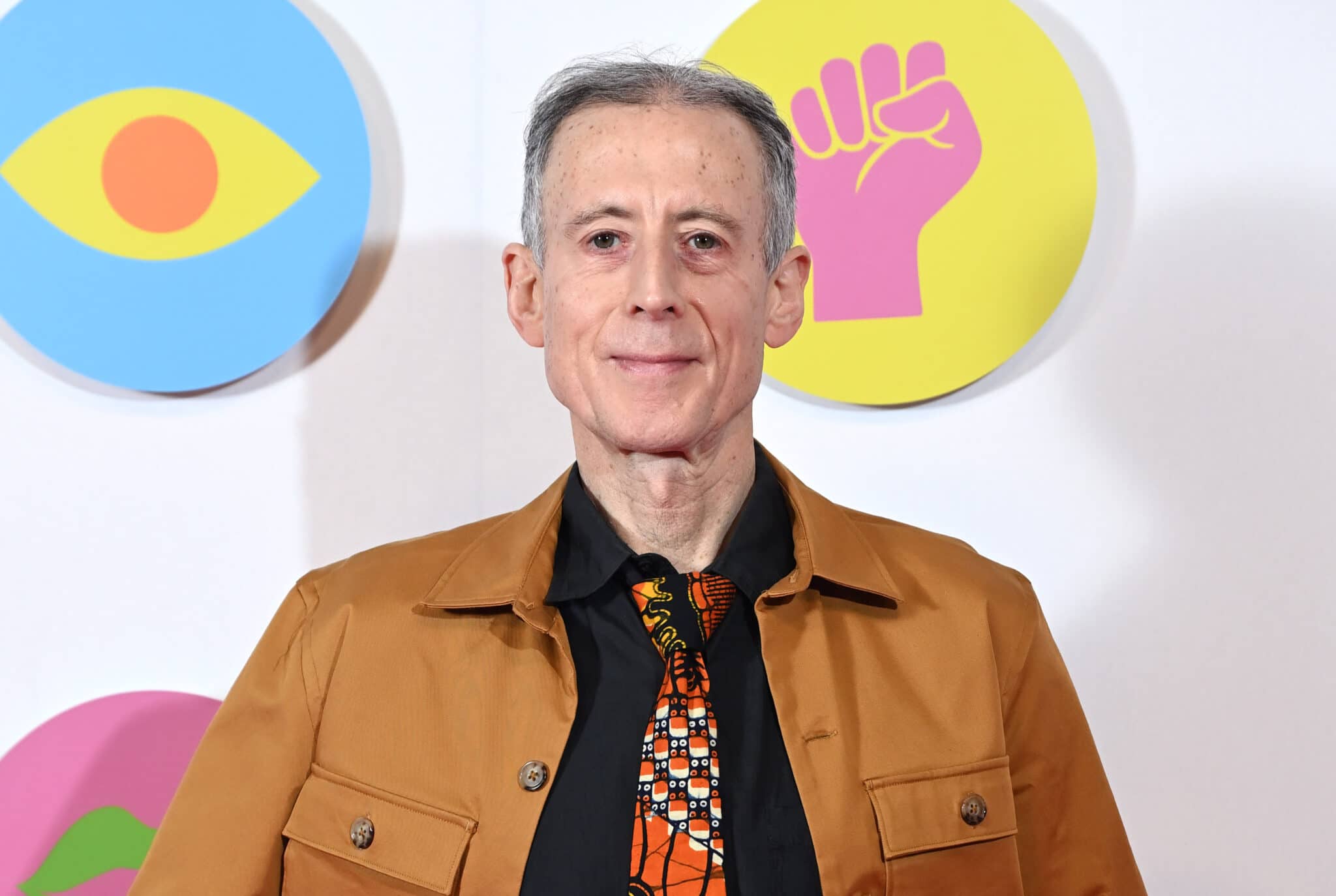

LGBTQ+ rights activist Peter Tatchell says John Wolfenden’s support for limited decriminalisation amounts to a “de facto reiteration of support for anti-gay discrimination in law”.

“John Wolfenden is often hailed as a great liberal reformer. But he opposed homosexual equality and obstructed fellow committee members who proposed a more far-reaching decriminalisation,” Tatchell tells PinkNews.

“A cautious conservative, he described homosexuality as ‘morally repugnant’ on the BBC TV programme Press Conference. He wanted only small changes in the law. His report proposed a very partial law reform.”

Tatchell says Wolfenden’s own opinions on homosexuality dominated the committee’s deliberations, and that those attitudes contributed to what was a “half-baked, partial decriminalisation of sex between men 10 years later”.

“The report did not urge the repeal of anti-gay laws; merely a policy of non-prosecution in certain circumstances. The existing, often centuries-old, laws were to remain on the statute book under the heading ‘unnatural offences’ until 2003.”

Although Wolfenden’s proposal were deeply flawed, he set Britain on the long, slow path to further LGBT+ law reform

Tatchell also draws attention to the report’s fumbling of the age of consent, something which would go on to impact gay and bisexual men for decades to come.

The report recommended that the age of consent for homosexual acts be set at 21. Furthermore, it said the maximum penalty should be increased for a man aged 21 or over who was convicted of having sex with a man aged between 16 and 21.

Some of Wolfenden’s “homophobic” proposals were later incorporated into the Sexual Offences Act of 1967.

“Wolfenden was often an obstacle to progressive recommendations,” Tatchell explains. “On three key issues, he played a negative role.

“When committee members discussed the age of consent, Wolfenden was aghast to discover that seven wanted 18, one advocated 17 and only three supported his proposal of 21.

“In a committee session in 1955, Wolfenden indicated his belief that young men could be seduced and corrupted into homosexuality. He was adamant that he would never put his name to a report recommending anything other than 21 as the age of consent. He bullied and overrode the majority who favoured a lower age limit.

“Equally shocking, Wolfenden wanted to keep anal sex totally illegal in all circumstances, even between consenting adults in private. He also supported retaining the option of pushing ‘serious cases’ of anal sex with life imprisonment.”

Sixty-five years since it was first published, the Wolfenden report’s legacy couldn’t be much more complicated. While it was credited with helping change the law, it also meant that the systems that oppressed gay and bisexual men would only only continue to be enforced.

“Although Wolfenden’s proposal were deeply flawed, he set Britain on the long slow path to further LGBT+ law reform,” Tatchell says.

“He enabled most LGBT [people] to love discreetly in private and to meet and organise without the threat of arrest. That was progress.”