Monkeypox expert shares advice for queer men in monogamous and open relationships

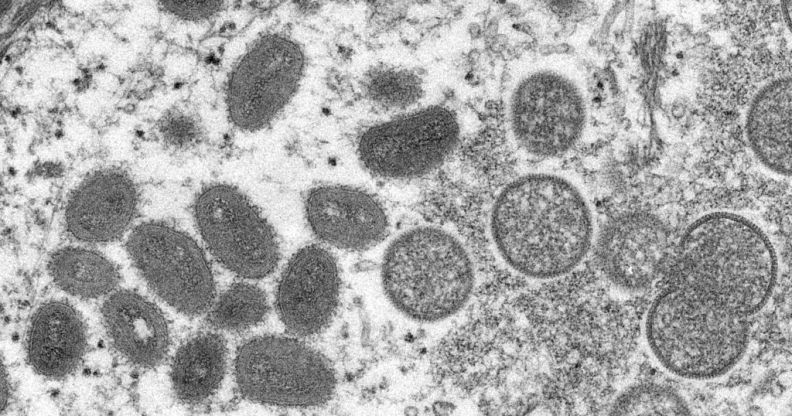

Microscope image of the monkeypox virus. (Getty/ Gado/ Smith Collection)

The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared monkeypox a “global health emergency”, sparking a rush of fear and panic among LGBTQ+ people.

The virus, once only detected in parts of Central and West Africa, has been spreading rapidly among gay and bisexual men in London and other cities across the UK for weeks. Thousands of cases have so far been detected worldwide, with a major study finding that transmission is occurring almost exclusively among men who have sex with men.

Luckily, the smallpox vaccine also offers protection against monkeypox, and those who are deemed at the highest risk of contracting the virus are being urged to get jabbed to protect their own health and to drive down transmission across the board. In the UK, official guidance states that gay and bisexual men – along with other men who have sex with men – who have multiple partners, or those who participate in group sex, should seek out a vaccine.

Right now, the focus is on getting vaccines to those at the highest risk of contracting monkeypox. That means gay and bisexual men who are not sexually active, or those who are in monogamous relationships, are not advised to get vaccinated – at least until more vaccines become available.

Not all gay and bisexual men are currently at high risk of contracting monkeypox

“While it’s true that the infection is predominately being transmitted in some sexual networks of gay and bisexual men, it doesn’t mean that every person who’s gay or bisexual is at risk of acquiring monkeypox,” Mateo Prochazka, an infectious disease epidemiologist with the UK Health Security Agency, tells PinkNews.

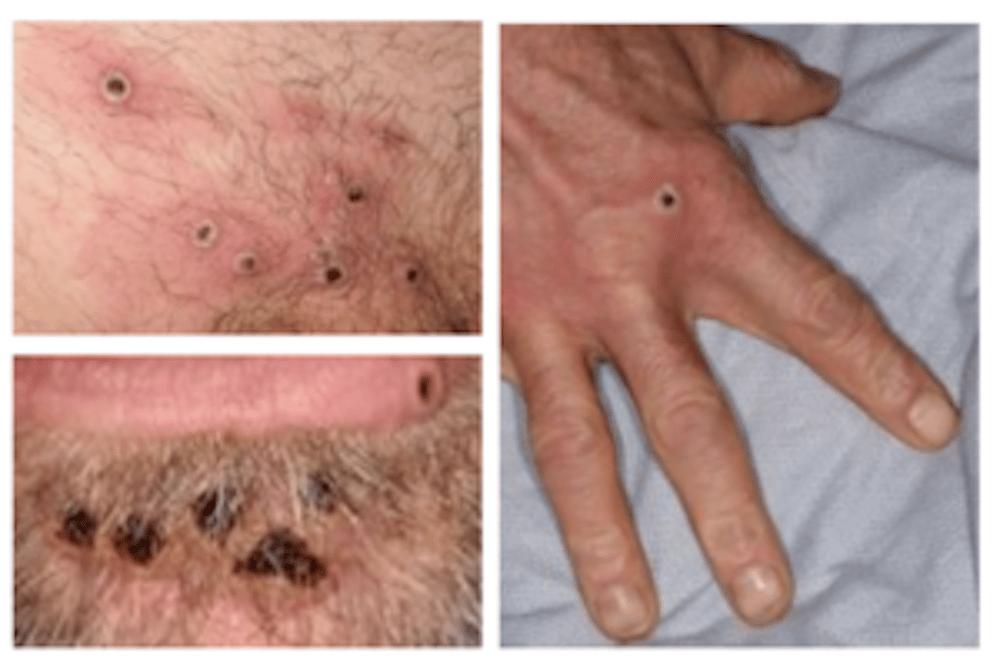

Monkeypox scabs. (CDC/Getty Images)

“Infections don’t care about your sexuality, they care about your behaviour. In that sense, it’s usually people who are participating in group sex or who are having multiple new partners that are at increased risk of acquiring infection.”

Prochazka says the UKHSA’s current strategy is to seek out those on PrEP, those who have had an STI over the last year, and people with HIV who have multiple sexual partners for vaccination.

“People who don’t fall within these categories at this stage should not feel like they need to come forward and get their vaccine just yet because we’re prioritising vaccination to those at the highest risk,” he says.

Prochazka says it’s “completely reasonable” for gay and bisexual men who don’t fall within those categories to be feeling worried – but he points out that, when there are vaccine shortages, those at the highest risk must be prioritised.

If people are monogamous, if people are only having one stable sexual partner and their relationship is not open, it’s unlikely that they will acquire monkeypox.

“While it’s true that those of us who are in monogamous relationships feel we could be exposed to monkeypox by being in the same social spaces as some of our peers, the truth is that from interviewing hundreds of cases we know that the majority of people are getting the infection through sexual contact,” Prochazka says.

Monkeypox lesions. (UKHSA)

“If people are monogamous, if people are only having one stable sexual partner and their relationship is not open, it’s unlikely that they will acquire monkeypox. It’s not to say that at some point the vaccination strategy won’t be widened or made more broad to make sure that everyone, even those at very low risk, are being offered a vaccine, but at this stage it’s the most sensible thing to wait and make sure that people who are at the highest risk are given the vaccine first.”

Some in open relationships are choosing to close them temporarily

Prochazka says the UKHSA isn’t interested in “policing” people’s sexual behaviours, but he also points out that it may be sensible for those in open relationships to consider closing them temporarily while they wait for vaccination.

We don’t really have an interest in policing people’s behaviours – we want people to be equipped with the right information.

“I have so many friends who are in open relationships and this summer they have decided to close their relationships because that’s the way they are managing risk,” Prochazka says. “I think it’s a completely personal decision but in my opinion it’s a sensible one. This doesn’t have to be a permanent change but it could be a short change while we wait for the vaccine to kick in at the population effect and to make sure that we’re protected as a community. Then again, it’s always going to be a personal choice. We don’t really have an interest in policing people’s behaviours – we want people to be equipped with the right information.”

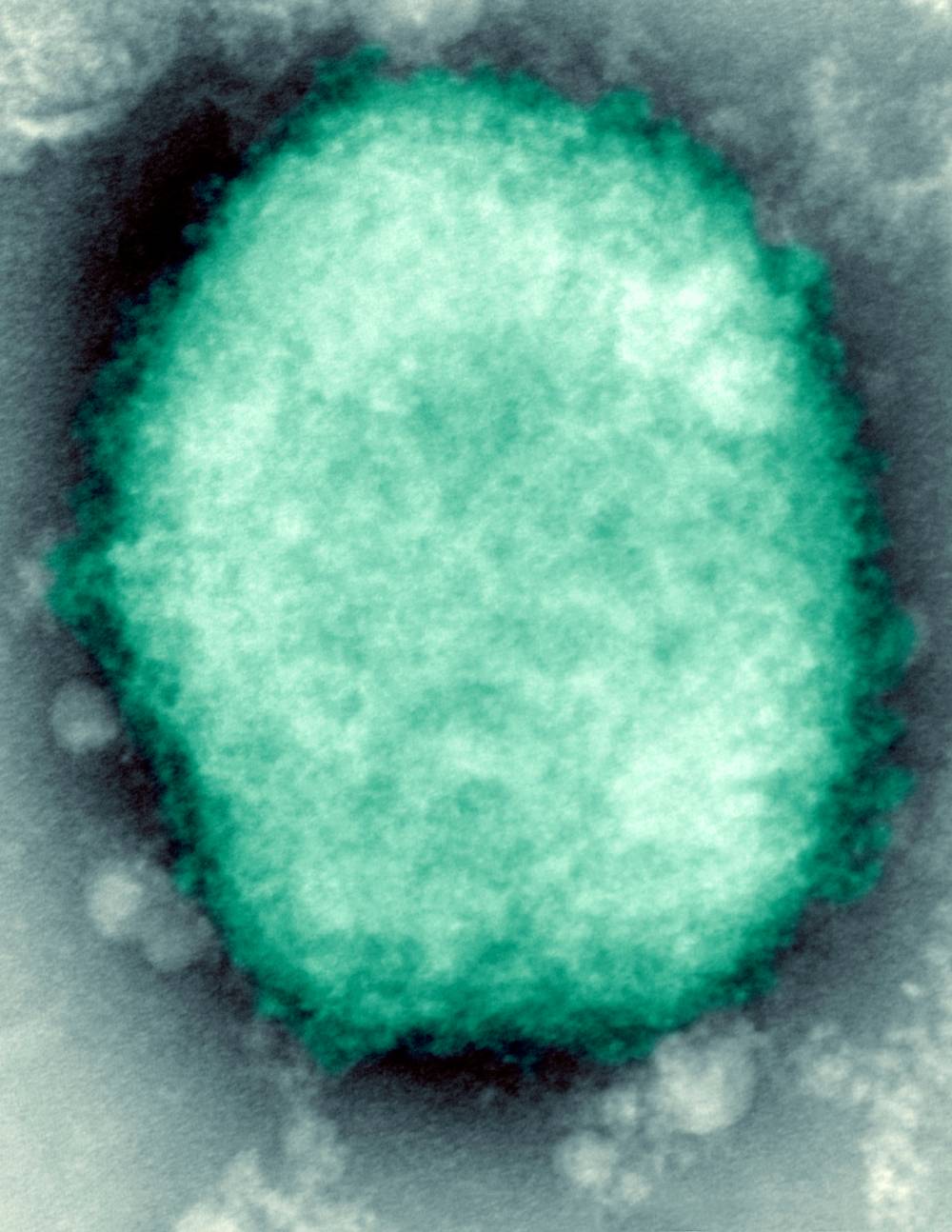

Monkeypox virus present in human vesicular fluid. (BSIP/UIG Via Getty)

Prochazka says people should continue being “very proactive” in engaging with the conversation surrounding monkeypox.

“Keep talking to your peers and remember the value of word of mouth when talking to people in your community because that really helps us to move things forward.”

Prochazka is also conscious that there may be people at high risk of contracting monkeypox who might not be fully open about their sexuality – some could be afraid of queuing publicly at pop-up centres out of fear that doing so could effectively out them. Still, he says the fear of stigma mustn’t act as a deterrent to people are most in need of the vaccine.

“This is an infection that can be quite unpleasant, it can be quite painful. You shouldn’t let the fear of stigma end up hurting your health and your wellbeing in the end because that’s exactly how stigma operates.”

Fraser Wilson, head of media and PR at the Terrence Higgins Trust, tells PinkNews that vaccine shortages are making a “horrible situation” even worse, with many queer people afraid for their health and wellbeing.

It’s just about relaying the facts, reaching the people we need to reach, especially gay and bisexual men in London.

“If you are identified as part of that most at risk group, definitely go forward and get that vaccination,” Wilson says. “As an organisation what we’re trying to do is to push for even more procurement.”

He’s also concerned about the impact stigma could have on vaccination uptake.

“It’s just about relaying the facts, reaching the people we need to reach, especially gay and bisexual men in London and other cities and encourage them to get a vaccine when they can and to get tested if they have any doubt,” he adds.

“It’s a careful balancing act and we’re doing our best to try and give that health information in a way that doesn’t perpetuate stigma.”