How a forgotten legal squabble defined ‘legal sex’ and set the course of trans rights for decades

English fashion model and former Merchant Navy sailor April Ashley pictured signing the marriage register with her husband Arthur Corbett (1919-1993) on the day of their wedding in Gibraltar on 11th September 1963. (Simpson/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty)

The 1970 case of Corbett vs Corbett began as a property dispute between former spouses – the sort of mundane occurrence that fills courtrooms every day. Yet its influence would extend farther than any of the parties involved could have foreseen.

Its unintended consequences brought the category of ‘legal sex’ into being and set the course of trans rights in England well into the 21st century.

Although the judge said he had no interest in defining legal sex, his ruling did just that for four decades across at least eight countries and five continents, in cases spanning from sex work to rape to gross indecency.

In 2004 it prompted the passage of the Gender Recognition Act, triggering the debate that continues to dominate discussions of trans issues in British media today.

Trans model and actress April Ashley was born in 1935, in what she would later describe as a ‘dockland slum’ of Liverpool, and died in December 2021 at the age of 86. She underwent gender confirmation surgery in Casablanca in 1960 and began a career in modelling, appearing in British Vogue and playing a small part in the 1962 film The Road to Hong Kong starring Bing Crosby and Bob Hope. In 1961 she was outed by the tabloid Sunday People with the sneering headline: “‘Her’ Secret Is Out”. Her name was subsequently dropped from the credits of The Road To Hong Kong.

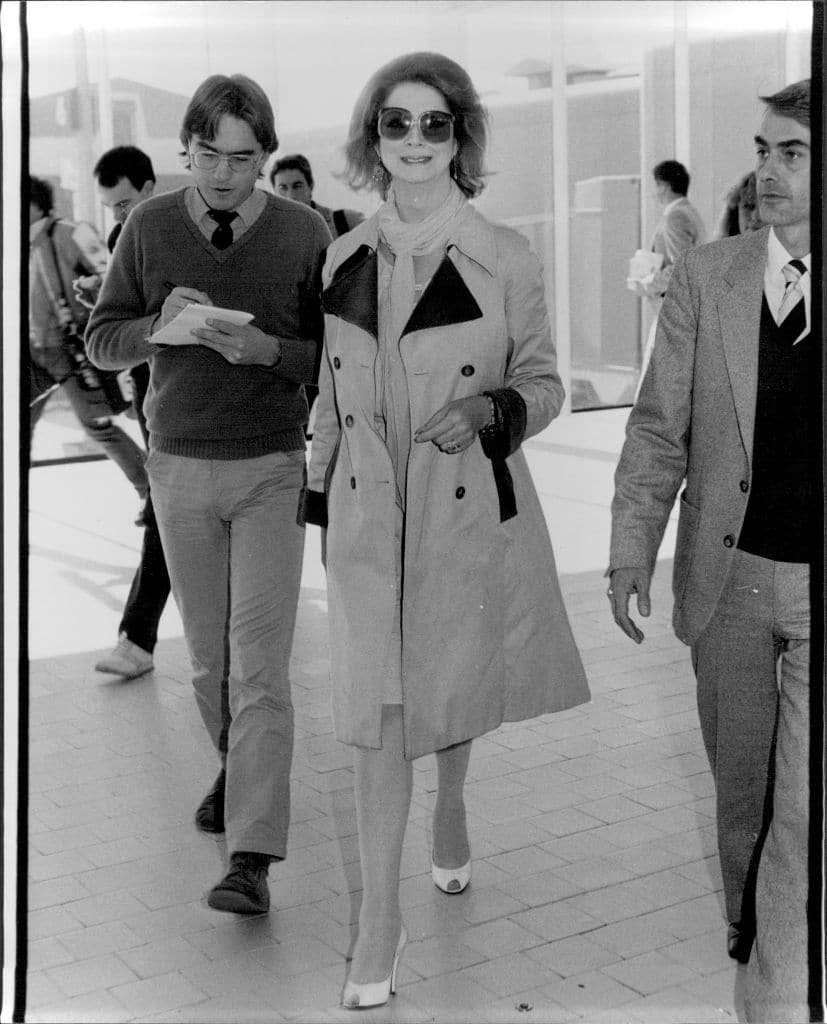

April Ashley. (Trevor James Robert Dallen/Fairfax Media via Getty)

In 1960, Ashley was introduced to the honourable Arthur Corbett, the future third Baron Rowallan. Corbett knew that Ashley was trans. In fact, he had a history of gender non-conformity himself, and was attracted by what he saw as the ‘success’ of her transition, saying of Ashley’s appearance: “The reality was far greater than my fantasy.”

In his letters to her, he spoke of the pleasure he felt in thinking of her as the future Lady Rowallan. Their relationship was the subject of much tabloid coverage, with headlines like “A Peer’s Son And The Sex Change Girl”. But their marriage in 1963 was short-lived – the Sunday Mirror reported that they had lived together as spouses for just 14 days.

Ashley requested that Corbett pay her maintenance in 1966. Corbett responded by challenging the legal validity of their marriage, petitioning for nullity on the grounds that she was “a person of the male sex”. Legal sex as a category came into being for the pettiest of reasons – because an aristocratic man wanted to avoid the obligation to support his ex-wife.

The scales were tilted in Corbett’s favour from the beginning. He was an Eton-educated future baron, and Ashley was a working-class trans woman. The judge, Mr Justice Ormrod, was, Ashley wrote, “disconcerted by me. He never once looked me straight in the eye but glanced furtively in my direction and mumbled his references to me as if they were distasteful to him. His behaviour towards me was contemptuous.”

The case involved a total of nine medical witnesses arguing about the particulars of Ashley’s body. April Ashley underwent repeated medical examinations, including a ‘three-finger test’ to determine whether her vagina could accommodate a ‘normal-sized penis’. She was subjected to a battery of invasive questions about her body, including whether before surgery she had ever had an erection or ejaculated. Ormrod reported, with scant sympathy, that she “refused to answer either question and wept a little”.

Ormrod’s decision in February 1970 ruled that the marriage was invalid because Ashley was ‘born male’. He was clear that he had no intention of defining ‘legal sex’, writing: “The question then becomes what is meant by the word ’woman’ in the context of a marriage, for I am not concerned to determine the ’legal sex’ of the respondent (Ashley) at large.”

He did not view it as incongruous that Ashley be recognised as a woman in some circumstances – such as on her passport – but not within a marriage, arguing that “sex is clearly an essential determinant of the relationship called marriage, because it is and always has been recognised as the union of man and woman.” He was only interested in determining what ‘woman’ meant in the context of heterosexual marriage, in a time where same-sex marriage was neither legally recognised nor widely discussed.

Despite Ormrod’s clear statements to the contrary, his judgement came to be used as a de facto definition of legal sex. The criteria he set out to determine sex for the purposes of marriage became known as the ‘Corbett criteria’, and, as academic Christopher Hutton put it, “provided subsequent judges with a short-cut to the determination of legal sex.”

The Corbett ruling was quickly incorporated into law. For example, the National Insurance Commission used the Corbett ruling to consolidate a pension policy that took only sex assigned at birth into account.

Before Corbett vs Corbett, there was no category called ‘legal sex’. Nor were there any rules determining when people could change the sex on their documents. Some trans people had their sex changed on identity documents as early as the 1940s. Trans man Michael Dillon described going to the Labour Exchange during the Second World War to have his female identity card replaced with a male one:

With the poker-face back on and on the defensive I went to get a new identity card at the Labor Exchange, prepared for grins and curiosity.

‘Oh, yes,’ said the man behind the counter, ‘we have had quite a lot of these applications,’ and made me out a new card without batting an eyelid! How common was it? I am none the wiser on that point now.

We still don’t know much more than Dillon did about how many trans people quietly had their documents changed in this way. But we do know of other trans people who had at least some of their documents amended prior to the Corbett judgement.

Historian Mar Hicks found records of an unofficial procedure at the Ministry of Pensions for amending trans people’s sex – they would simply record that a ‘mistake’ had been made in identifying sex at birth. By the 1960s, they had a secret record of hundreds of trans people.

The Corbett criteria were used in cases far outside the parameters of marriage. In 1983, a trans woman was charged with multiple offences relating to sex work, some of which only applied to men. The prosecution successfully used Corbett to argue that she was legally male, and she and her co-defendants – including her disabled husband – were convicted of more severe offences than if she had been recognised as female.

Corbett’s standards were not universally agreed with overseas. In 1976, the Superior Court of New Jersey heard a trans rights case that was similar to Corbett. A trans woman requested alimony from her cisgender ex-husband; he argued that their marriage was invalid. The judge ruled in the trans woman’s favour, on the basis that the trans woman had had genital surgery and thus could engage in vaginal sex.

April Ashley holds her Member of the British Empire (MBE) medal which was awarded to her by Queen Elizabeth II in 2012. (Sean Dempsey – WPA Pool/Getty)

While far from progressive, this was a significant improvement on the Corbett ruling, which opined that sex involving Ashley’s vagina (which Ormrod called a ‘cavity’) was not vaginal sex, writing “the difference between sexual intercourse using it and anal or intra-crural intercourse is, in my judgment, to be measured in centimetres”.

In England, the Corbett judgement was not contradicted for decades. The 2001 trans rights case of Bellinger vs Bellinger, involving a marriage between a trans woman and a cisgender man, was instrumental in the passing of the Gender Recognition Act. The Court of Appeal declined to validate the marriage as lawful, but issued a declaration of incompatibility under the Human Rights Act, acknowledging that the existing legislation deprived her of her right to marriage.

The Gender Recognition Act was passed in 2004, granting trans people with a gender recognition certificate (GRC) the right to marry in their acquired sex. Practically speaking, however, the process of getting a GRC – and therefore the ability to marry in their affirmed gender – remains inaccessible to many.

Corbett vs Corbett began as the messy break-up of a marriage, and ended by entrapping trans people in a legal double-bind from which it would take them over 30 years to free themselves. Ormrod’s decision not only made Ashley, and people like her, incapable of legally marrying a man – it rendered them unable to marry anyone.

Per Ormrod’s argument, Ashley was incapable of consummating a marriage as a woman. But she also could not have married a woman, since, having had her penis removed, she could not consummate a marriage that way either. Twelve days after the judgement, Ashley wrote: “It means that the law of Britain forbids me ever to share my life with anyone, forbids me to love or be loved, puts me apart from all the ordinary men and women in the human race.”

April Ashley’s case is a prime example of the ways in which trans people’s lives are weaponised against us.

Ormrod’s decision had less to do with clearly defining legal sex and much more to do with protecting the institution of heterosexual marriage. Yet 50 years on, the British press is still engulfed in discourse defending the sanctity of legal sex. Ormrod’s decision alone did not create that category – it developed over the decades through various interpretations of his ruling, which changed to reflect changing scientific understanding. So why should today’s debates so strenuously resist further changes?

In Bellinger vs Bellinger, the House of Lords recognised that the law as it stood was no longer fit for purpose. It has been almost 20 years since then and, in my view, we are in another such position today. Trans people applying for a GRC still need to provide medical, legal and bureaucratic evidence so that a panel of strangers they will never meet can adjudicate the validity of their identity.

There are still plenty of barriers to getting a GRC. One of the most significant hurdles is the requirement for a diagnosis of gender dysphoria. Trans healthcare in the UK is in a spiralling state of crisis, with every NHS gender identity clinic having years-long waiting lists. Many people, therefore, would have to turn to private healthcare to fulfil these conditions.

As a trans man myself, I often think about what it must have been like for Ashley to live for 50 years knowing the impact her case had had on the lives of trans people all over the world.

In 1982 she said: ‘’I felt stripped, denuded, humiliated in front of the whole world and I thought I was going to die. To have been through all that, and to find myself at the end of it a non-person. Did you know that if we are raped, we have no rights?”

Her case is a prime example of the ways in which trans people’s lives are weaponised against us. Ashley couldn’t just be a woman going through the break-up of a marriage – the intimate details of her life and body became fodder for the court and the press. Trans people are still subject to intense scrutiny, and we still have to petition a board of strangers to have our gender recognised, a right which cisgender people have by default.

The question remains whether it was any more appropriate for an anonymous panel to adjudicate my sex in 2020 than it was for Justice Ormrod to rule on April Ashley’s sex in 1970.