How Freddie Mercury’s tragic passing saved lives in the fight against HIV and AIDS

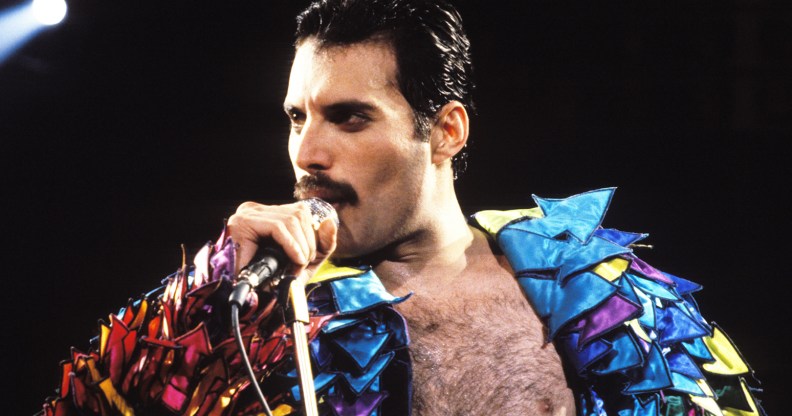

Freddie Mercury. (Steve Jennings/WireImage)

On 20 April 1992, some of the biggest names in the music industry descended on London’s Wembley Stadium to remember their friend Freddie Mercury.

It was a momentous occasion – George Michael, Liza Minnelli, David Bowie, Annie Lennox, Axl Rose and countless other famous figures turned up to pay their respects to the rock music legend who had died just months before following a long battle with AIDS. Crucially, the concert also raised vital funds for HIV research – and it helped change cruel, discriminatory ideas people had about the virus and its prevalence among queer men.

That time is explored in the powerful BBC 2 documentary Freddie Mercury: The Final Act, which airs on Saturday (27 November) to mark 30 years since the singer’s death. The film reflects on the final months and years of the Queen frontman’s life – and it culminates with that history-making concert. By now, most people will know the general story of Freddie’s life – he was a wild, vivacious figure whose music touched hearts and filled arenas, but AIDS brought his life to a close in 1991.

But Freddie Mercury: The Final Act isn’t interested in rehashing that well-worn story – instead, the documentary tells the story of Freddie’s life by contextualising it alongside the experiences of other queer people who lived through the AIDS epidemic. The film also demystifies the celebrity surrounding Freddie, and reminds viewers that behind the famous figure was a man who was loved by his friends and family.

Dan Hall, a producer on the documentary, was in his late teenage years when Freddie died – and he remembers just how awful a time it was to be gay. He came out just weeks after the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert aired – seeing that celebration of the singer’s life gave him the courage to open up about his identity.

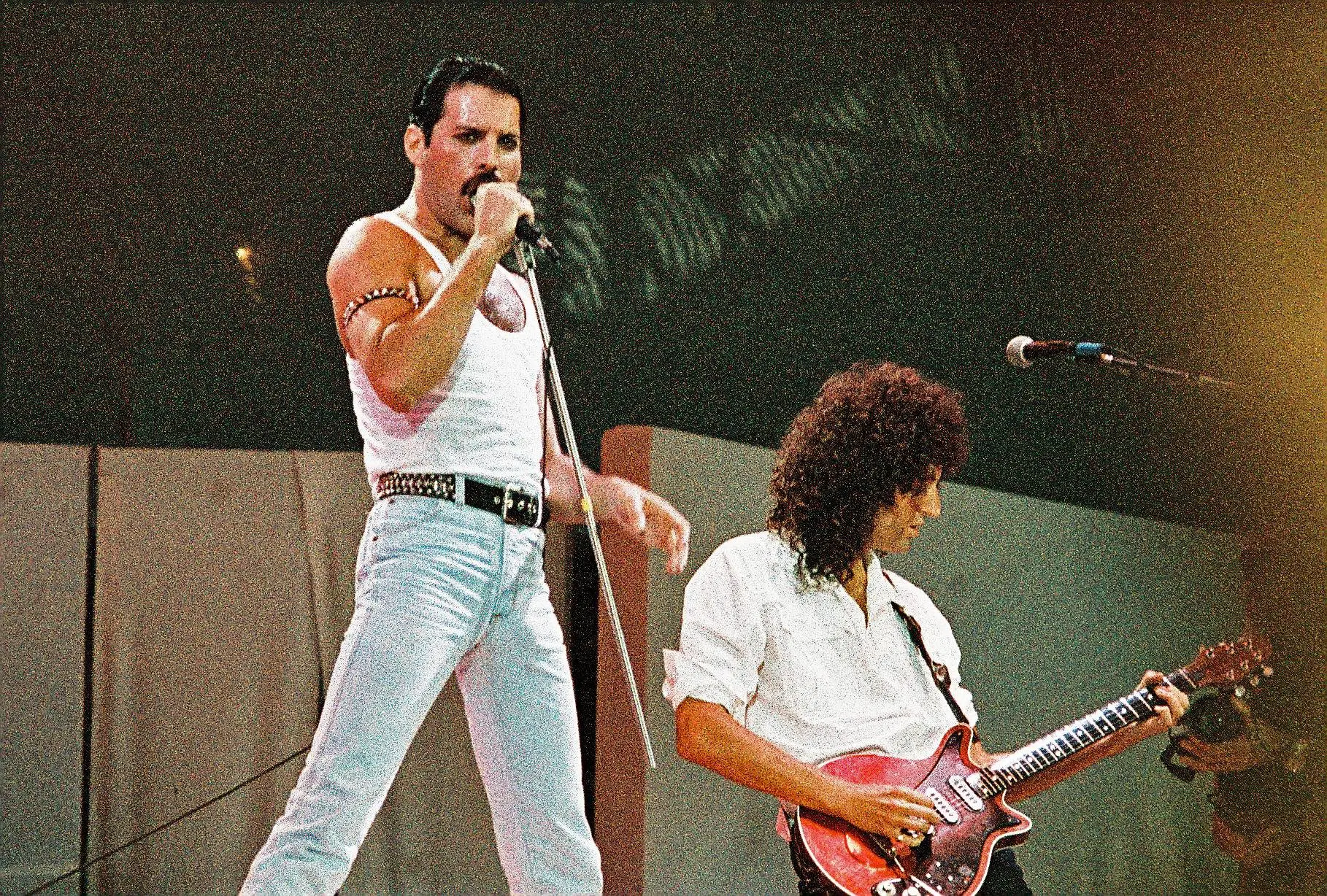

Freddie Mercury of Queen performs on stage at Live Aid on July 13th, 1985 in Wembley Stadium. (Pete Still/Redferns)

“It was horrible being a sexually active gay adult in the early ‘90s,” Dan explains. “It was a really s**tty place to be, and you kept sitting there trying to pretend that condoms were fun and sexy and they just weren’t.

“People were dying still, so the concert, by its very nature [was significant]. People were wearing red ribbons – that was the thing that seemed incredible to me. I saw these metal heads on a stage wearing red ribbons, and it was just like, my goodness – shining a light where society tells me there should be shadow and shame. It felt exciting. It’s only as I’m saying this, I’m just realising, it was the first time I had an awareness of straight allies, and that was incredibly important.”

Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert ‘changed the conversation’ around HIV and AIDS

James Rogan, director of Freddie Mercury: The Final Act also remembers the concert airing. He was just 11-years-old when it happened, but he remembers how meaningful it was.

“It was such a big deal at the time – for an 11-year-old, it was my first encounter really with Queen and I totally fell in love with their music,” James says. “I had grown up in the era of AIDS where it was a dark shadow, it was all tombstone adverts. It was something that was spoken about with a lot of fear, and I remember the concert as something that changed that conversation. So I was curious to go back to see if that was the case. I think what we found out was the focus shifted with the concert – it was a moment of acknowledgement of what had happened to so many people in a very public way. The more we got into it, the more emotional it became.”

The original concept was that the film would focus specifically on the concert itself, but the end result is a different beast altogether: instead, the documentary tells the story of Freddie’s life, death, and – more broadly – the impact of the AIDS epidemic.

He didn’t want to upset people, and he was also simply a very private man.

“A sort of ‘making of’ was the original plan, but quite quickly in discussions that James and I were having, our thoughts were that we had seen a million and one different documentaries about lines of cable, and how many lights and this and that, and actually, if you’re going to do an interesting ‘making of’, you do a programme that is about the DNA of the concert – why was there a need to do an awareness concert? Why was it important? And then we studied those reasons,” Dan says.

Dan was excited to bring his own experiences as a gay man who lived through the AIDS epidemic to Freddie Mercury: The Final Act, but he’s also glad the documentary wasn’t made exclusively by queer people.

“I certainly found it very useful having a straight director because otherwise, I think it can run the risk of falling into its own echo chamber,” he says. “In addition to that, I didn’t realise until we started to make this film, through conversations with James, about how gaslit we were as a queer community. There are things that I didn’t think were a big deal because they were just what life was like, and James would be like, ‘Oh my God, that’s awful!’ And you realise as a gay person that there were things that were unacceptable. I guess in order to survive, you just get used to it. So having an outsider look at these things and saying, ‘That’s not acceptable,’ was really useful, and I think really has added to the story.”

Freddie Mercury: The Final Act tells the stories of other people who lived through the AIDS epidemic

One of the ways James and Dan confronted the horrors of that era was by incorporating interviews with people who had been directly affected by the AIDS epidemic. Freddie Mercury: The Final Act tells the story of the singer’s final months, but it also sets the scene and reminds people what a terrible time it was to be queer through first-person testimony.

“For me, that was important because this wasn’t a music documentary – it was more of a documentary musical, in the sense that Freddie expresses himself throughout the documentary through the medium of song,” James explains. “There are gaps in Freddie’s life – he was very private, so there are big gaps in what people know about, in terms of him getting tested, the treatment that he had. He didn’t want to upset people, and he was also simply a very private man.”

James is adamant that they wanted to approach Freddie not as a celebrity, but simply as a gay man living through a traumatic, terrifying time. That’s one of the reasons they decided to include other people’s stories about AIDS – they wanted to understand what was happening to people like Freddie at the same time.

“The story of AIDS is still a story of prejudice and also, lack of access to medication for groups of people that may be less well off, or those who are alienated within society. I don’t think we should dance around the point – we should be very angry that there are 680,000 people dying a year from AIDS-related diseases when, if you’re on the right medication, it’s not even transmissible. It’s not an acceptable reality, but we have, for some reason, on a global level accepted it. Even in the UK there’s still a lot that could be done.”

Much has changed in the years since Freddie’s death, but prejudice and harmful views persist when it comes to sexual health. Dan still faces discrimination within the queer community – and dating apps are often a minefield when it comes to oppressive attitudes.

“When I was on Grindr, I used to get slut shamed for being on PrEP,” he says. “There’s such ignorance, it’s ridiculous. Within the queer community – as if we don’t get enough trouble outside of it – we’re getting slut shamed for taking a medicine that prevents us from becoming HIV positive. Don’t even get me started on the queer community not even knowing what U=U is – there is no excuse. There used to be in the ‘90s – you could be like, ‘Well I don’t go to bars so I can’t pick up leaflets,’ so there was an excuse to be ignorant. But there is absolutely none now and it really pisses me off.”

James admits he didn’t know about U=U – which refers to the scientifically proven fact that people with HIV who are on effective treatment cannot pass the virus on – until he came to this film. He was “surprised” by some of the advances that had occurred, and shocked to learn that he didn’t even know about them.

“My point of view is that the situation has been managed in the UK with medication, and the outcome is people can live a full and healthy life. That’s a really positive thing,” he says. “But as a disease, it’s still a huge cause of death globally, and it’s an unnecessary cause of death.

“When it was in the ‘80s and ‘90s in the UK, there was certainly a sense that this is happening to gay people, this is happening to drug addicts and haemophiliacs – it was an ‘other’ thing, and I think that ‘other’ mentality has shifted now that it’s happening mostly in sub-Saharan Africa and places in Asia, and also still massively in the African-American community.

“We all have to ask ourselves why we are accepting this situation.”

HIV still disproportionately affects ethnic minorities

This is echoed by Dr Mark Pakianathan, a HIV consultant who appears in Freddie Mercury: The Final Act. He was working as a junior doctor on a HIV ward in Edinburgh in the early 1990s when Freddie died.

“I definitely went through medical school with this thing emerging,” he says. “I didn’t know much – I was 23, working really hard, long hours. I’ve gone on a long journey since then and I’ve re-evaluated things as I’ve grown up, and I’ve reflected on all the things I did to cope to get through it – some of it unhealthy, just to get through the trauma and the fear and the anxiety. I survived not necessarily with the best coping skills, but it got me through at the time, but there are things I’ve had to address later in life and grieve for, actually, in my 40s and 50s.”

Looking back on that time, Mark thinks Freddie’s death helped bring HIV and AIDS “out of the shadows and into the light”.

If you look at HIV diagnoses, if you’re white, gay, male, you’re more likely to be diagnosed early and get on treatment.

“I guess if you really loved the music of Queen, how could you suddenly hate the person who was your idol? Perhaps that had an important effect – it kind of softened people’s attitudes. Even if you weren’t that into his music, you would watch him and see that he had such a commanding presence.”

Freddie Mercury (1946-1991), singer with Queen, standing in front of a drum kit as he sings into a microphone on stage. (Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty)

It has been 30 years since Freddie Mercury died, but Mark says there is still a long way to go in the global fight against HIV.

“There’s a further way to go in some communities compared to others,” he says. “If you look at HIV diagnoses, if you’re white, gay, male, you’re more likely to be diagnosed early and get on treatment. Diagnosis rates in this group have fallen sharply. But if you’re Black or Asian, then the rate of fall is less. You’re much more likely to be diagnosed late if you’re an ethnic minority.”

Mark admires Freddie Mercury for publicly stating that he had AIDS at the very end of his life because he knows just how hard it must have been.

“He must have agonised over it forever,” he says. “He let it all hang out at the end which I think is where liberation comes from… That announcement was so important – it allows you to reflect on the music and the words of the last song. I still think about it sometimes and get moved to tears about what he’s singing about through that lens.

“I have a lot of compassion for his history, and our collective history, because he was singing about some of that experience that we all went through.”

Freddie Mercury: The Final Act – BBC Two – 9pm, Sunday 27th November. Also available on BBC iPlayer.