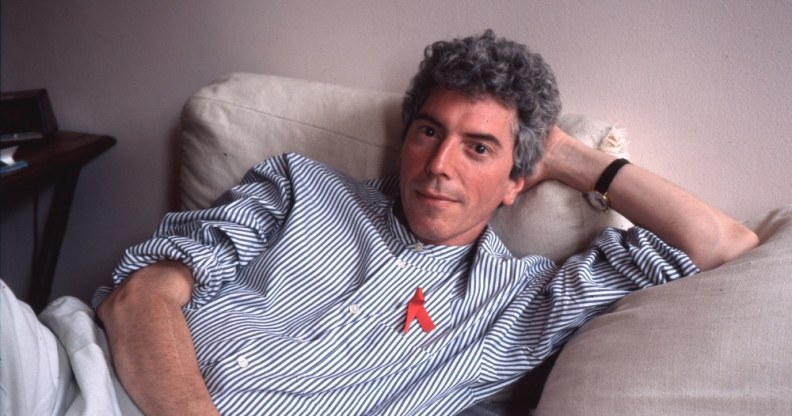

AIDS activist and creator of the red ribbon, Patrick O’Connell, dies aged 67

Patrick O’Connell. (Thomas McGovern/Getty images)

Patrick O’Connell, a venerable AIDS activist who sought to smash stigma with awareness campaigns such as the iconic red ribbon, has died.

O’Connell passed away aged 67 of AIDS-related causes, his brother Barry confirmed to The New York Times.

Living with HIV for 40 years, he spent much of his life fronting campaigns to better educate the public about what it means to live with HIV/AIDS.

The son of a wire lather and secretary, O’Connell was born 12 April, 1953, in post-war New York City.

For much of the 1980s, O’Conell’s life was filled with rented black funeral suits and friends fearful of what was then a dooming diagnosis. By the end of the decade, AIDS had become the leading cause of death for men aged between 25 and 44.

In 1991, O’Connell formed Visual AIDS, a collective of artists and advocates who used a borrowed art gallery space to design exhibitions that forced the public to reckon that the disease.

“We had no choice,” he said in a 2003 interview with the BBC. “We had to do something with our professional lives.

“The East Village art scene felt like it was disappearing overnight because of AIDS. All our colleagues around the country were dying.”

No wonder. The White House was, at the time, almost indifferent to the virus’ rampage across the US and treated it more as a punchline than a public health emergency.

That’s when O’Connell had an idea: a small way to encourage the world to reckon with the disease that was destroying so much of the LGBT+ community – a red ribbon.

That same year he launched the Ribbon Project and with it, an unwavering and defiant symbol of AIDS activism.

To O’Connell, the colour red was as rousing as it was morose. It symbolised, he told the BBC, blood. It is “the colour of passion” and is “vibrant and attention-getting”.

“The yellow ribbons from the Gulf War were still all around,” he told The New York Times in 1992. “We noticed that they could mean anything from ‘I care about young people who have gone overseas’ to ‘I support Bush.’

“We wanted that kind of leeway, too, something that could mean ‘I hate this government’ or just ‘I care about people with AIDS’.”

In the two weeks before the 1991 Tony Awards, the 15 artists involved in Visual AIDS oversaw the making of thousands of grosgrain ribbons which were delivered to the Minskoff Theatre.

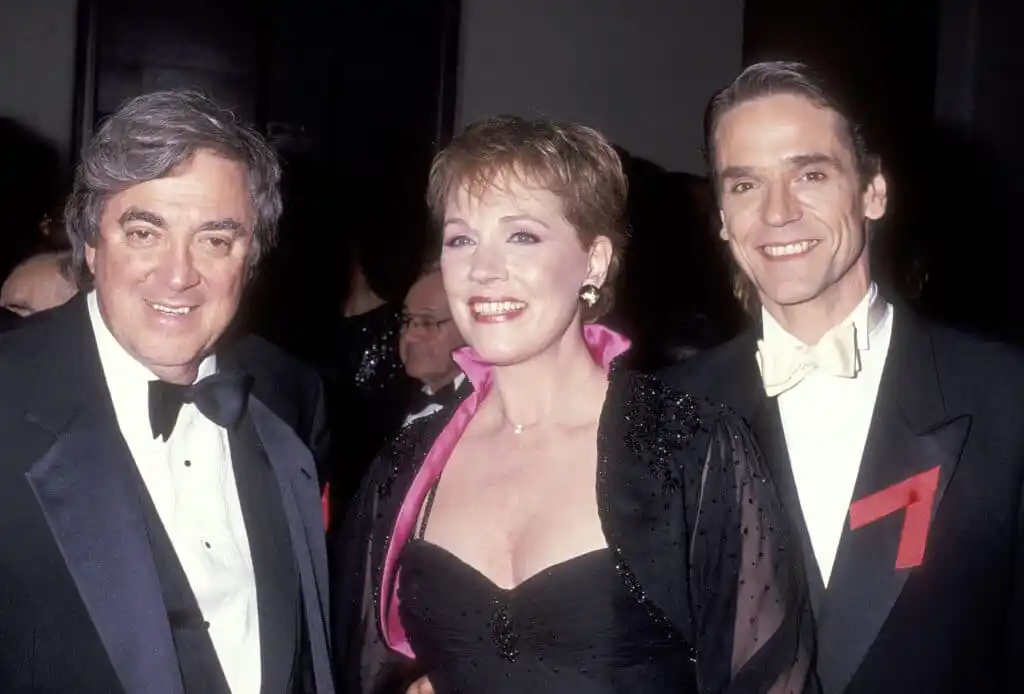

As the awards were beamed into homes across America, host Jeremy Irons walked on – and he was wearing a red ribbon.

(L-R) Producer Walter C Miller, Julie Andrews and Jeremy Irons attend the 45th Annual Tony Awards on June 2, 1991. (Ron Galella/Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images)

Soon enough, whether it be pinned on a dress worn by Elizabeth Taylor or printed on United States Postal Service-issued stamps, the red ribbon was everywhere.

O’Connell’s death comes after that of Larry Kramer, the ACT UP agitator who fought against policy-makers to take the disease seriously, and Nita Pippins, who was something of a mother figure to countless AIDS patients.

“It is hard to be prideful of something that was generated by such frustration and sorrow,” O’Connell reflected of his decades-long work in AIDS activism to the BBC.

“I would give anything, I would give back all this attention if I hadn’t lived through these decades of AIDS.

“All the people who died so young, these talented people. Now I know only one person alive from my 20s.”