Acclaimed author George M Johnson on their unflinching, heartening tale of growing up queer and Black in America

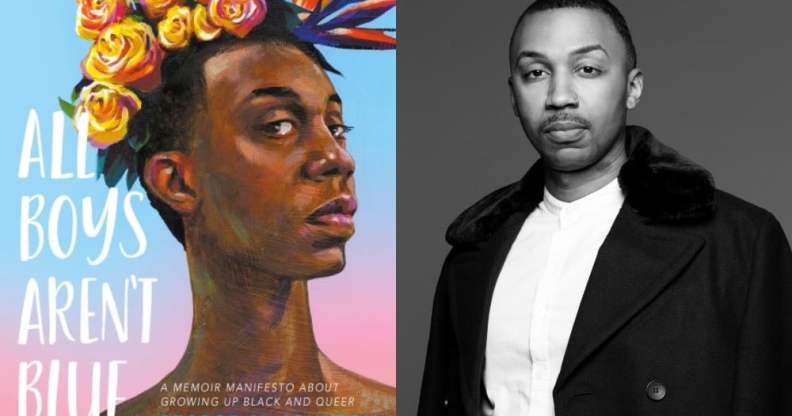

George M Johnson is the author of All Boys Aren’t Blue. (Penguin)

George M Johnson’s debut book All Boys Aren’t Blue is on its way to becoming a bona fide classic, winning critical acclaim and adoration, and is being adapted for TV with Gabrielle Union.

Part memoir, part manifesto, All Boys Aren’t Blue tells Johnson’s story of growing up queer and Black in America. Often, it’s an unflinching account: getting their teeth kicked out by childhood bullies; learning to quieten their queerness to get by; being sexually abused when they were 13 by an older cousin. But it’s also a joyful tale: of a multi-generational family that embraced Johnson (and other queer family members, including a cousin who came out to them as a trans woman); of finding a second family at university; of coming into their sexuality as an adult and “losing their virginity twice” (topping and bottoming). The title reflects the layers of identity Johnson explores as they recall their story: their Blackness, their gender, their sexuality, among other things.

It’s the level of detail that makes the book so striking – it’s aimed at a young adult audience, but Johnson isn’t afraid to “go there”, as they put it – and it’s why the book has become something of a phenomenon, accumulating glowing review after glowing review and being optioned for television by Gabrielle Union, who Johnson bonded with as her daughter Zaya Wade navigated her own queer, trans identity.

PinkNews: All Boys Aren’t Blue delves into some difficult subjects. Was it important for you not to sugar-coat those experiences for your young audience?

George M Johnson: One of the things I thought was: anything that I leave out saves me from feeling shame or embarrassment, but it harms the person reading it. It was about finding balance: can I withstand a little bit of feeling ashamed, guilty? Because with some of the stories it’s like, “Oh, this person knows all of this about me.” They [leave me] very, very vulnerable, and they’re very telling, but at the end of the day I would feel much worse if I didn’t tell a story and something like it happened to someone else, if that story being in the book could save someone else. That was really how I pushed my way through all of the difficult topics. You can’t heal what you don’t name, and so I wanted to make sure I named as many things as boldly as possible.

When you’ve met young readers, what have their responses been?

It’s been amazing. I’m always blown away by the amount of knowledge that kids have around these subjects, and the amount of knowledge that they have around themselves. You have these meetings, and the kids are like, “I identify as pansexual”, or, “I identify as bisexual” at 16 and 17. Some of the language they use now, we just didn’t have 15 or 20 years ago. And it’s amazing, number one that you can do that, and number two that y’all have family lives and families that know and y’all are really living.

So it’s beautiful to just see that, but it’s also great that they get to see a possibility model of what they can be, who they can be, that we still exist in the world and it doesn’t always have to be tragedy at the end. We do have a lot of tragic stories in our community, but some of us are working to make sure that we also can showcase and give visibility to some of our greater stories.

You even say in the book that you feared you might get pushback. But it’s had such a phenomenal impact, do you feel vindicated for telling your story the way you did?

I don’t know yet! I feel like the other shoe hasn’t dropped yet, because I feel like enough people who are conservatives in this country haven’t realised that this book exists yet. I do have a feeling that once kids go back to school, should my book be placed into school systems, in certain states that are more conservative than others, that is when we will see. There is still time for this book to be banned.

You’re working with Gabrielle Union on turning All Boys Aren’t Blue into a TV series. How did that come about?

I wrote an article about their family very early on [before Zaya came out as trans], and about the importance of supporting LGBTQ children. And it’s funny, because sometimes I write about celebrities, but I rarely tag them. But for some reason I tagged both of them [Gabrielle and Dwyane Wade, on social media]. It was like, maybe they do need to read this so that they know: hey, there are people out here that exist that can help with this, because we’ve lived it. They both read it and sent me really nice messages, and from there Gabrielle and I formed this really great relationship.

A few months later I sent them the book, and from there we optioned it. We’ve been working really hard – I’m learning on-the-fly script-writing and treatment-writing and all of these different things. But we’re getting much closer to solidifying what the show will be about. Hopefully within the next couple of months, we will have some news. Not hopefully – we’re going to manifest that in the next couple of months, someone will buy the show.

You’re continuing your story in your second memoir, how will that differ?

We Are Not Broken is the story of Black boyhood. Especially in the United States, Black boys are robbed of innocence –Black children in general – we’re looked at by the police and by systems as adults as early as the age of five. I wanted to write a story about the fact that I grew up with three other Black boys – my little brother and my two cousins – and my grandmother, Nanny, who was the centre of our universe, and how we had adventures and we did get to be kids, and how more Black kids should have that opportunity to be kids.

But also, I wanted to touch on some of the tough subjects around gender roles and masculinity. I always say All Boys Aren’t Blue is basically the micro, that’s me and the tentacles around me, whereas We Are Not Broken is gonna give you the macro look. It’s really a love letter to my grandmother, Nanny, and her wisdom, ensuring that her words get to go into the world in the same way that all the other greats do.

It’s clear that family dynamic is important to you, is that something that you’ll continue to centre in your work?

Yes. It’s interesting, even when we think of like movies and TV shows, we don’t have a lot with the Black family dynamic. We used to – in the early 90s there was the boon of A Different World, The Fresh Prince, The Cosby Show… but we don’t have a lot of that anymore. I wanted to make sure that I was putting something into the world where it just showcased the Black family fully and in totality. It’s necessary that we put that content out there and it’s necessary that the stories are told through a Black lens. I think that’s why my book is doing so well, because it’s not told through a white gaze. Even as a Black writer, you could still be trying to tell stories for the appeasement of white people, and I just have no desire to do that. Will white people read these stories? Absolutely. But will it be told for the appeasement of them? Absolutely not. It is told through a Black lens for for Black people. Because we just don’t have enough of that.

All Boys Aren’t Blue is out in paperback, published by Penguin Books.