Why wasn’t the AIDS crisis taken as seriously as COVID? Because it killed gay people, not old people

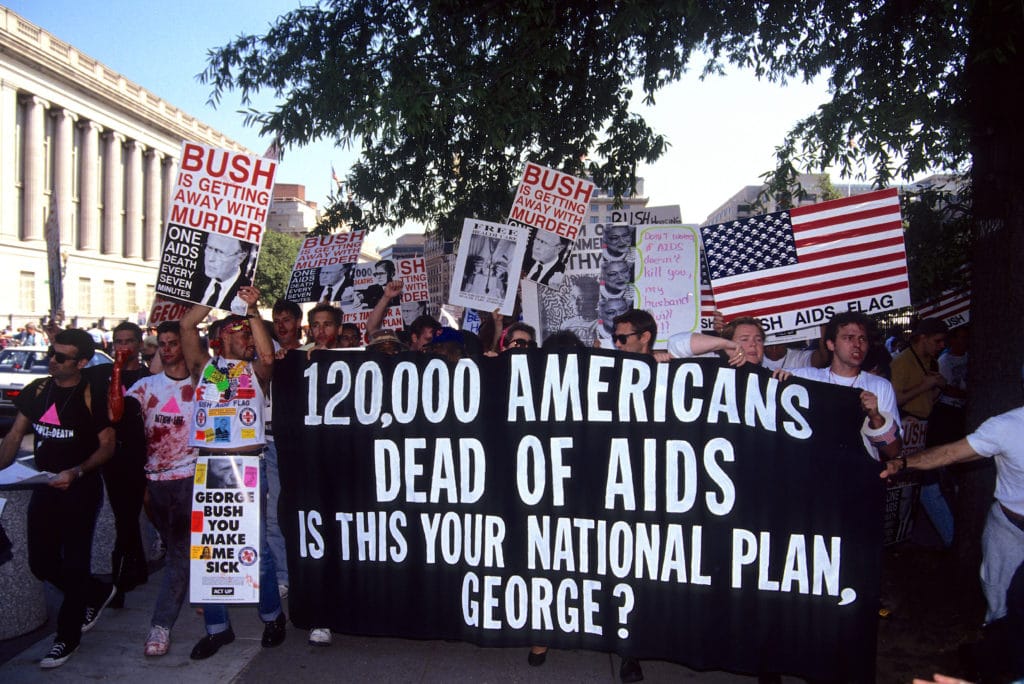

ACT UP demonstrators chanting at AIDS rally, New York City. (Joe Sohm/Visions of America/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Scott Beasley, an assistant editor at Sky News, writes for PinkNews about the toll the AIDS epidemic took on his family in the 1980s and beyond, and the parallels that can be drawn between HIV/AIDS and COVID-19.

I was seven when I watched my uncle dying in St Lukes-Roosevelt hospital in New York City.

Simon was only 36 and it was the 90s. I remember asking someone what a lump on his neck was. It was just his Adam’s apple, but he was so thin it stuck out painfully.

I’d never seen anything like it before, growing up in rural Herefordshire, England, as I was at the time. But in New York – and San Francisco, London and other big cities with a large gay community – it was horrifyingly common.

Just a couple of weeks later he was dead, another victim of the AIDS epidemic.

My parents couldn’t tell me the truth, shell shocked by grief and shamed by the stigma that surrounded the disease. They said he had cancer, it must have seemed easier and a way to shelter me.

They didn’t want me to go to New York when Simon pleaded with my Mum to let me travel over, knowing he didn’t have long to live. I demanded to go and I’ll always be glad that I did.

Five years earlier my other uncle, Neil, had died of AIDS, too. He was 33.

The Broderip AIDS ward at Middlesex Hospital, 1987. (Nigel Wright/Daily Mirror/MirrorpixGetty Images)

In just a few short years my mum had lost both of her brothers – my grandmother both of her sons. They were young gay men, dead in their thirties, a lifetime ahead but victims of a disease labelled and dismissed as the “gay plague“.

Neil worked for Elton’s John’s manager, John Reid, depicted in the film Rocketman. Elton wrote of Neil in his recent autobiography: “The first person I knew who died of AIDS was my manager’s assistant, Neil Carter.

“He was a lovely young man, and I was distraught when I learned he had the disease. Three weeks later, he was dead. His was the first plaque I placed in my chapel.”

I only understood what really happened to ‘the boys’ as I got older: slowly working things out, finding documents and putting together hints from family conversations, or the lack of them.

I found anguished letters to the New York Department of Health, pleading for hope as much as a wonder treatment that didn’t yet exist.

Heartbreakingly, Simon was probably just a few months or short years from surviving long enough to benefit from the new drugs coming on stream.

He was by any measure an extraordinary young man – the first in our family to go to university, the youngest director of a merchant bank in London who went to work in Hong Kong in the financial boom of the 80s.

He was dashingly handsome and, from everything I’ve learned, incredibly popular and fun to be with. I recently unearthed some new photos of him, travelling to far-flung places, surrounded by friends, always with a drink in hand. The photos reminded me of, well, me.

By 1991, AIDS was the biggest killer of young men in New York. By 1994 it the biggest killer of young men in the United States.

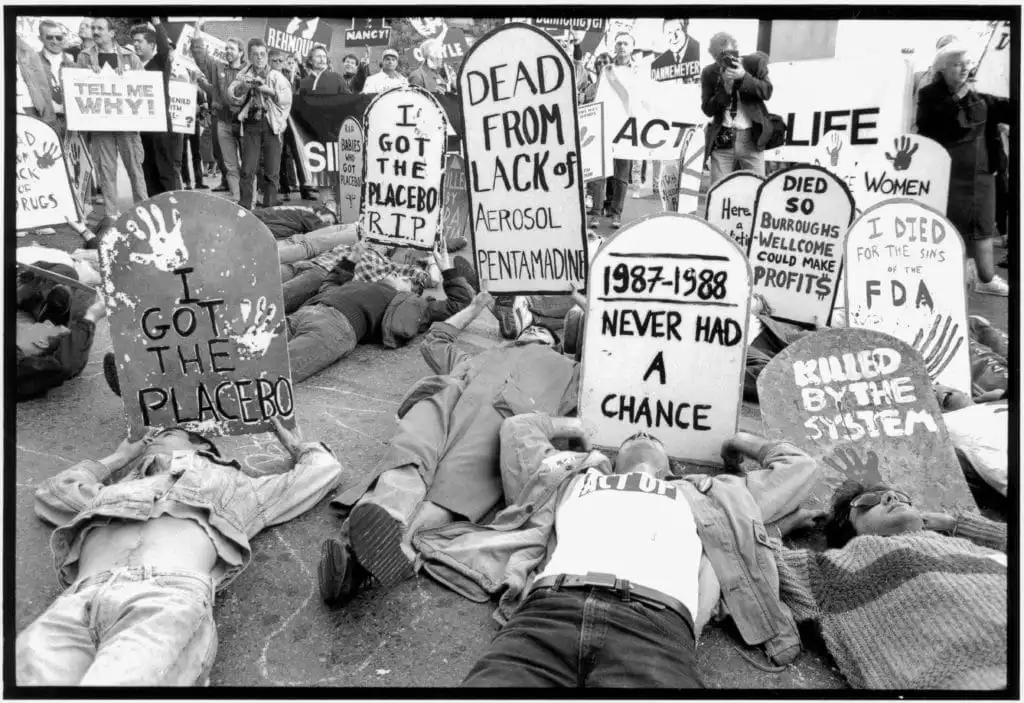

Members of AIDS activist group ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power). (Catherine McGann/Getty Images)

In 1995 more than 8,000 people died in one year alone in New York City and 40,000 across the US. It was an epidemic by any measure. But the world didn’t respond as it has to COVID-19.

As I came to understand that I was gay too, I realised the sheer weight of the stigma – I’m sure it’s one of the reasons I didn’t come out until I was much older.

The family story is a microcosm of what happened to the gay community in those years and later. A whole generation of young men was wiped out. Those that survived – or were still to – were traumatised and brutalised by the effects.

The fantastic news we have an effective and safe vaccine against the virus that causes coronavirus made me think of the starkly different approach taken to the early years of HIV.

In the months since COVID-19 was discovered, we’ve put the world on a war footing, our way of life on hold and thrown the resources of the most powerful nations on Earth at the disposal of science to fight it.

Lockdowns, travel bans, quarantine, mass testing. Billions of pounds spent on treatment, information campaigns, medical research and hundreds of billions more to support the economy. Minute by minute, breathless blanket media coverage.

ACT UP targets US president Bush at the White House. (Mark Reinstein/Corbis via Getty Images)

The World Health Organisation says speed is the best defence against a new virus – acting fast to erect defences to protect society and individuals. The global response has been unprecedented and after just a year we’re administering a vaccine that could typically take years or even decades to develop.

I’m no epidemiologist and they’re very different diseases, but when HIV emerged it wasn’t old people it killed, it was gay people. And that meant the world didn’t care.

Governments didn’t act. The media didn’t cover it. Or if it did it was in an embarrassed or disgusted tone.

Any coverage was dehumanising and cruel. So hundreds of thousands died. They were usually young gay men or trans or people of colour. And many in society, and government, thought that was no bad thing.

The necessary billions of dollars didn’t flow for years – it was left to small groups, individuals and charities, fighting against indifference, intentional neglect and worse. More than two million people have died of coronavirus so far – it’s an awful toll.

But we’re on the brink of having the tools to control the disease. The HIV virus was isolated and identified in 1983. 800,000 people died from HIV/AIDS in 2018 – 35 years later.

To date the number is so far into the tens of millions it’s hard to be sure.

In 1988 the iconic AIDS activist group ACT UP protested the Food and Drug Administration because it was so slow to approve new drugs. Its ‘drugs into bodies’ campaign sounds a lot like the clamour to get ‘vaccines into arms’ now.

ACT UP protesters close the Federal Drug Administration building to demand the release of experimental medication for those living with HIV/AIDS. (Peter Ansin/Getty Images)

Last year the FDA approved a coronavirus vaccine faster than ever before – in a matter of months. This health crisis shows just how quickly the private sector and government can act if the will – and money – is there.

Bill Clinton first called for an HIV vaccine back in 1997 and said it should be in place 10 years later. It isn’t, of course, some 23 years later.

Many people will say they are different diseases, different means of infection and pose a different threat to the world economy – they’re right. And – eventually, through gritted teeth – many countries put in place ground-breaking information campaigns, like ‘Don’t Die of Ignorance’ in the UK.

But HIV was still an extraordinary killer: it had racked up almost 500,000 victims – killing nearly 60 per cent of everyone it infected – in the US alone by 2000, the same year president Clinton declared the disease a threat to national security.

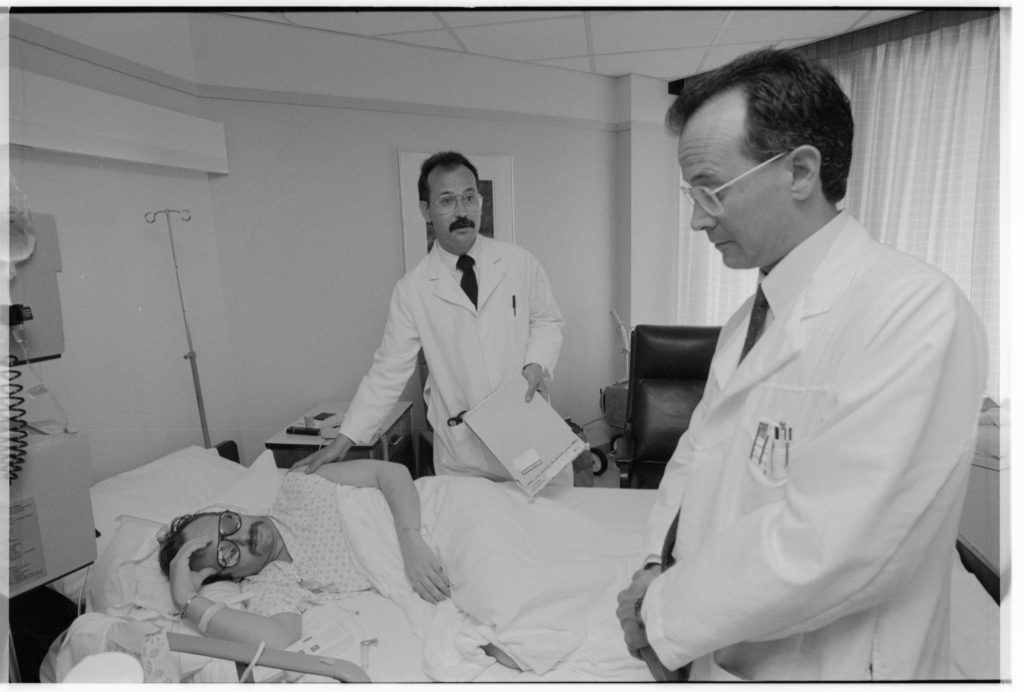

Physicians Thomas J and Timothy J Smith, identical twins, meet with a patient suffering from AIDS at a hospital room. (Roger Ressmeyer/CORBIS/VCG via Getty Images)

Of course, it did pose a real threat to one part of the global economy – Africa, where it spread with devastating efficiency and brutally cut life expectancy across the continent, wiping out a generation of young workers.

But like young gay men and minorities, the economies of Africa do not come high up the list of priorities for global powers.

When I was young it was pretty much widely accepted – or expected at least – that gay men who had the temerity to have sex would die from HIV/AIDS.

Now in developed countries they don’t – with effective, safe and easy treatment HIV positive people lead full, healthy lives and don’t pass the virus on.

It’s more than 25 years since Simon died and looking at those photos of him, it was harrowing to realise that the only big difference between us is that I get to live.

I can’t help but feel if the first victims of the disease weren’t people like him and Neil, the world would have reacted very differently. Maybe we’d have acted with the speed we have to COVID-19 and he’d still be here now.