Holocaust Memorial Day: How the Nazi pink triangle became a defiant symbol of gay rights

Gay men wearing the pink triangle in a Nazi concentration camp. (Stock image)

As the world marks Holocaust Memorial Day, PinkNews remembers all those in the LGBT+ community that were persecuted by the Nazis — and how the pink triangle, used to identify gay or bisexual men in concentration camps, became a symbol for gay rights.

When Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party seized power in Germany in July 1933, the dictatorship moved to persecute and murder minority groups, including Jews, LGBT+ people, the Romani people, and political prisoners.

Beginning in 1933, the Nazis built a network of concentration camps throughout Germany, where “undesirable” groups were detained, including Jewish people and gay men.

This persecution continued following the outbreak of World War II in 1939 and, between 1941 and 1945, the Nazi Party systematically murdered six million European Jews — as part of a plan known as “The Final Solution to the Jewish Problem” — in extermination camps and mass shootings. This genocide is referred to as the Holocaust, or the Shoah in Hebrew.

In total, up to 17 million people, including thousands of gay and bisexual men, were systematically killed at the hands of the Nazis.

Holocaust Memorial Day is held on January 27 annually — marking the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest Nazi death camp — and remembers the millions of people killed by the Nazis and in subsequent genocides in Cambodia, Rwanda, Bosnia and Darfur.

Holocaust Memorial Day: Nazi persecution of gay men and the LGBT+ community

Under Nazi rule, the persecution of homosexual men intensified, although gay sex between men had already been illegal since 1871.

It’s estimated that the Nazis imprisoned more than 50,000 gay men, including an estimated 5,000 to 15,000 men who were sent to concentration camps, according to research by historian Rüdiger Lautmann.

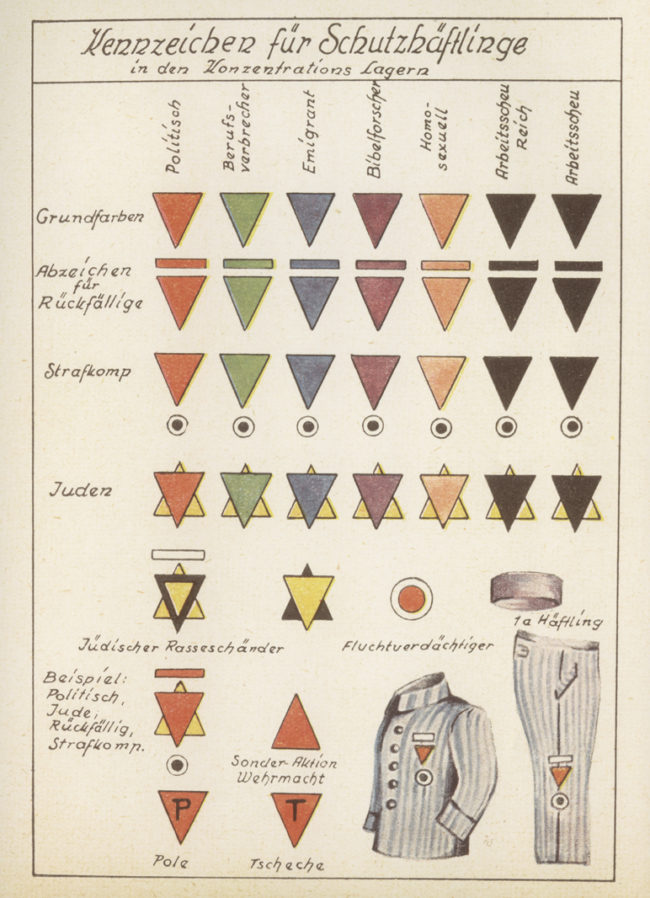

The classification system used for the uniforms of inmates—including the pink triangle for homosexuals—in Dachau concentration camp in Upper Bavaria, southern Germany. (HMDT/USHMM)

Although sex between women was not officially illegal in Nazi Germany, lesbians were also persecuted. Benno Gammerl, a lecturer in Queer History at Goldsmiths, University of London, tells PinkNews that the persecution of lesbians is “much harder to trace” because they weren’t included in the penal code and there was no specific categorisation of gay women in concentration camps (although some were made to wear a black triangle badge used to denote “asocial” prisoners).

Trans people, too, are known to have been persecuted under the Nazis, including being sent to concentration camps. According to Transgender Day of Remembrance, in 1938 the Institute of Forensic Medicine recommended that the “phenomena of transvestism” be “exterminated from public life.”

Again, Gammerl acknowledges that there have been demands for further research on the plight of trans people under the Nazis, saying: “At the moment, we simply [do] not know enough yet.”

Holocaust Memorial Day: The pink triangle in Nazi concentration camps.

In Nazi concentration camps, a pink triangle was used to identify some gay men. Gammerl, who describes the pink triangle as a “Nazi invention,” says it is “not quite clear” why the Nazis used the colour pink for this purpose.

In concentration camps, LGBT+ inmates were subjected to starvation and forced labour, as well as facing discrimination from both SS guards and fellow inmates.

Pierre Seel, a gay survivor from the Schirmeck-Vorbrück concentration camp near Strasbourg, who passed away in 2005, recalled one traumatising incident in his memoir. Seel wrote that a group of SS guards stripped his 18-year-old lover naked before releasing a pack of German Shepherd dogs which mauled him to death.

“There was no solidarity for the homosexual prisoners; they belonged to the lowest caste,” Seel wrote in his 1995 book I, Pierre Seel, Deported Homosexual: A Memoir of Nazi Terror.

“Other prisoners, even when between themselves, used to target them.”

Gay men were also subjected to torture — including forced sodomy using wood — and human experimentation at the hands of the Nazis. There are records of gay men being forced to sleep with female sex slaves, and lesbians being made to perform sex acts on males, as a form of gay conversion therapy.

There was no solidarity for the homosexual prisoners; they belonged to the lowest caste.

Still, Gammerl argues that, although “there is evidence that homosexuals received worse treatment,” the available records make it hard to claim with certainty that gay people were consistently treated worse than other inmates.

“It is difficult to make definite claims about homosexuals being at the very ‘bottom’ of the camp hierarchy,” he says.

“All inmates were living under the permanent threat of being beaten or raped or killed by guards and there was also violence happening between inmates, some of that was certainly also homophobic.

“So, I would say, all inmates lived horrendous lives far beyond what I can imagine.”

He stresses that, given that Jewish people predominately populated the concentration camps, “one certainly cannot say that homosexuals were treated worse than they were.”

All inmates were living under the permanent threat of being beaten or raped or killed by guards and there was also violence happening between inmates, some of that was certainly also homophobic.

Thousands of LGBT+ people are believed to have been murdered by the Nazis. However, the Nazis’ poor documentation of LGBT+ people means that historians have been unable to calculate an exact estimate. Lautmann has argued that the death rate for gay men could be as high as 60 percent of those detained in concentration camps.

Gammerl also stresses that some Jewish and Romani people killed by the Nazis may also have identified as a sexual or gender minority.

“When talking about numbers, it is important to bear in mind that part of the people who were persecuted as Jews, Communists, Sinti and Romanies, or as members of other groups the Nazis sent to concentration camps, that a certain number of these people may also have been LGBT+,” he adds.

Gay men after WWII and how the pink triangle was reclaimed as a gay rights symbol.

After the end of World War II, the persecution of gay and bisexual men continued. Same-sex sexual activity between men remained illegal in East and West Germany until 1968 and 1969 respectively.

Gammerl notes that, while authorities in East Germany were “more lenient” towards gay men after Word War II, the persecution of gay men in West Germany was “rather intense” in the decades afterwards with “large waves” of arrests in cities like Frankfurt.

“Same-sex desiring men and women had to make sure that they lived their lives not too publicly and for men there was the permanent fear of being sent to prison,” he explains.

Pink Triangle Park in San Francisco, where the pink triangle has been used to remember LGBT+ victims of the Holocaust.

There are also accounts of gay men being re-imprisoned using evidence obtained by the Nazis. For decades after the Second World War, the Nazis’ treatment of LGBT+ people went unacknowledged in many countries.

It took until 2002 before the German government apologised to the gay community and annulled the convictions of gay and bisexual men under the Nazi regime. In 2005, the European Parliament passed a resolution including homosexuals as part of those persecuted during the Holocaust.

Poignantly, as the gay rights movement gained momentum in West Germany in the 1970s, the pink triangle started to be used as as a symbol for marking the history of anti-gay violence.

In an act of defiance, the pink triangle was reclaimed — and often inverted, with the tip pointing upwards — as a sign of gay activism. It became known on an international scale during the 1980s, when a six-person collective, called the Silence=Death Project, used an inverted version of the triangle on posters that the group plastered around New York to raise awareness of the AIDS crisis.

The upwards pointing pink triangle was later used by the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) in its campaigns during the AIDS epidemic. It was also used in memorials to remember LGBT+ victims of the Holocaust in San Francisco, Amsterdam and Sydney.