India is poised for a gruelling battle for marriage equality. This inspiring couple are spearheading the fight

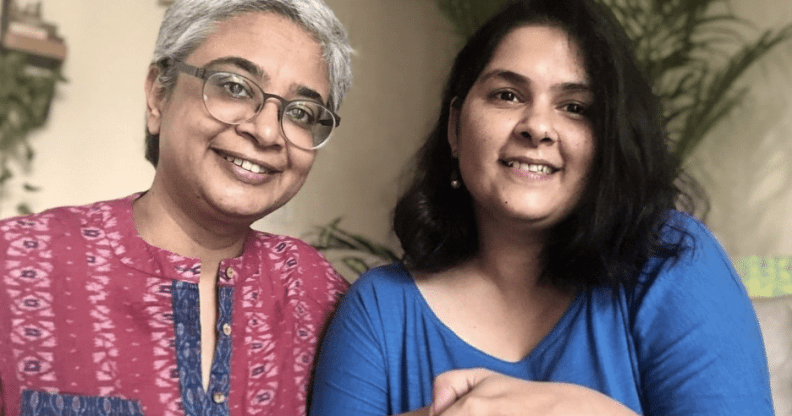

Kavita Arora and Ankita Khanna, who have been together for eight years, are spearheading the legal battle for equal marriage in India. (Twitter/Ankitakhanna)

Two women leading the charge for India to introduce equal marriage say they are “doing it for their younger selves”.

Kavita Arora and Ankita Khanna, who have been together for eight years, petitioned the Delhi court in October 2020 for the constitutional right to marry.

They, along with two other LGBT+ couples who have also petitioned the court, argue that without official recognition, they are “strangers in law”.

“We have created a great life together, but where is the legitimacy to that?” Khanna told TIME. Despite India decriminalising same-sex relationships in 2018, Arora and Khanna’s relationship has no legal status.

This means they can’t share property rights, make medical decisions for each other – something that suddenly became more pressing as the coronavirus pandemic swept the globe – and, in short, they lack the rights that heterosexual married couples in India take for granted.

“Marriage is not just a relationship between two individuals — it brings two families together. But it is also a bundle of rights. We wish to have the protection of the bundle of rights that a marriage provides, so that we are not trying to get authorities to acknowledge our relationship for every entitlement or right that married couples would get automatically,” Arora said, speaking to The Print.

“When we met with our lawyers, we were infused with renewed faith in the spirit of our Constitution and the legal process. And here we are.” @arorakavita @MenakaGuruswamy @arundhatikatju https://t.co/CqopByUbr6

— Ankita Khanna (@ankitakhanna) October 21, 2020

The legal fight for marriage equality in India is likely to take a long time – the judicial system is notoriously slow, religious groups are resistant and the top lawyer for prime minister Narendra Modi’s government has argued against equal marriage.

But the Delhi court has previously said it may be time to “shed our inhibitions” on the issue. It was the same Delhi court that in 2009 decriminalised same-sex relationships – only for that decision to be overturned by India’s Supreme Court in 2013.

The Supreme Court could similarly overturn the decision of the Delhi court in this case. But the road to appeal would be open, as it was previously, with the Supreme Court then decriminalising same-sex relationships in 2018.

India’s laws against homosexuality are a hangover of the British colonial era, which imposed laws against “carnal intercourse against the order of nature” in 1861. Prior to being colonised by the British, same-sex relationships and gender fluidity feature prominently in ancient Indian texts and sculptures.

Arora, 47, and Khanna, 36, are optimistic about their case – saying that it has, at the very least, brought the issue out into the open in a country where discussing LGBT+ topics is still considered taboo.

Their relationship “never felt criminal”, Arora said, adding that it was the urgency of the COVID-19 situation that spurred them into launching the case despite their reservations about being so publicly LGBT+.

The pair work together as a psychologist and a psychiatrist, supporting young people with their mental health, and saw first-hand how the 2018 decision to decriminalise same-sex relationships had “helped young people embrace their identity in all its complexity”, Khanna said.

“When I was 18, I wish I had an ordinary couple to relate to,” Arora said. “In many ways, I am doing this for my younger self.”

Khanna agreed, adding: “We did zoom-out [to] think about what this petition will mean for every young person we work with. That really was a turning point for us in this.”

The couple are not put off by what could be a very long fight.

“Social change takes eons to happen. So what?” Khanna said. “This is not just about us.”

“We are not seeing this as an event but as a movement,” said Arora. “And movements can’t be quantified by time.”