More than 400 ‘lost’ gay sex scenes by seminal British painter Duncan Grant found under a bed

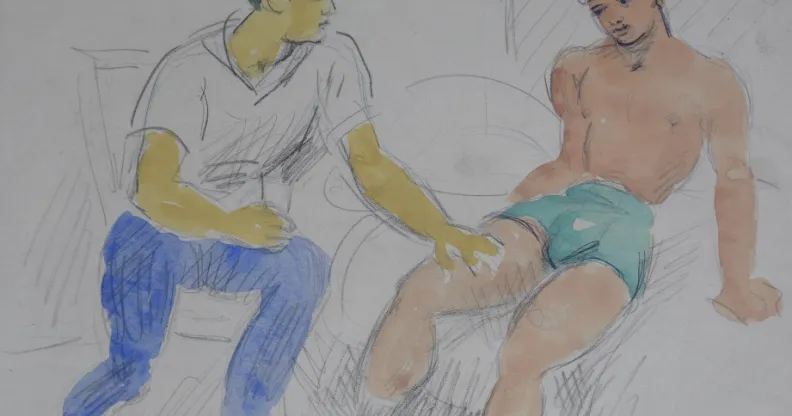

Untitled drawing, c.1946-1959, Duncan Grant (1885-1978), The Charleston Trust © The Estate of Duncan Grant, licensed by DACS 2020.

More than 400 “lost” paintings depicting gay sex by the British painter Duncan Grant have been discovered under a bed years after they first went missing.

Grant was a painter and designer and was famously a part of the Bloomsbury Group, an early 20th century group of English writers, intellectuals, philosophers and artists that included Virginia Woolf and E.M. Forster.

The painter had numerous love affairs with men throughout his life. Economist John Maynard Keynes once considered Grant to be the great love of his life.

On 2 May, 1959, Grant gave his friend Edward Le Bas a folder of his 422 erotic paintings, with the message “These drawings are very private”.

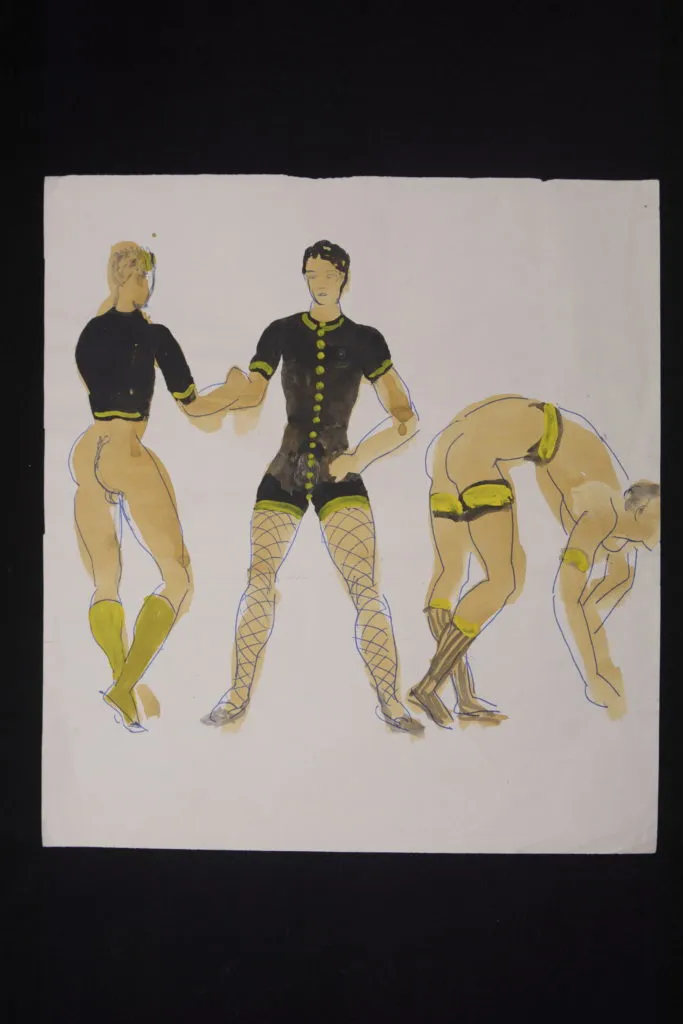

Inside was an incredible collection of erotic illustrations depicting gay sex and representing Grant’s fascinating with the male form and with queer sexuality.

It was widely believed that the erotic paintings of Duncan Grant had been destroyed.

It was thought that the drawings were destroyed by Le Bas’s sister following his death – however, they were rescued and passed from one person to the next over the course of 60 years before they eventually ended up in the care of theatre designer Norman Coates.

Untitled drawing, c.1946-1959, Duncan Grant (1885-1978), The Charleston Trust © The Estate of Duncan Grant, licensed by DACS 2020.

Coates decided to hand the collection over to the Charleston Trust, which runs the country house of Grant and Vanessa Bell as a museum dedicated to the Bloomsbury Group.

The erotic paintings were created in the 1940s and 1950s and were influenced by Greco-Roman traditions and contemporary physique magazines, according to the Charleston Trust.

Nathaniel Hepburn, director of Charleston, told The Guardian: “There haven’t been any joyous moments in 2020 for anyone run-in a cultural organisation, or many people in the world.

“But certainly getting that email, having that phone conversation and then seeing the drawings and realising how important they were going to be… it was certainly a high point of the year.”

He added: “They are, I think, a body of work that talks of love. Of course at a time they were made, that is a love that was illegal.

“He was never able to share the works. How we see them now will be very different.”

Coates said the paintings were “extraordinary” and “so in your face”.

“You can’t avoid them,” he added. “When I’ve occasionally brought them out to show selected friends after dinner, after the initial ‘My God’ exclamation at these very explicit drawings, they mellow… the sexual element really doesn’t dominate.

“It is the painting and the skill of his drawing and the aesthetic of it which negates the sexiness of them,” he said.

“It becomes irrelevant that the subject is what it is… it is a very odd feeling. It just becomes a beautiful collection of pictures.”