What is straightwashing? When Hollywood erases gay characters from films

From Orange is the New Black to Queer Eye, the representation of LGBT+ people and their issues in popular culture is improving fast.

One of Netflix’s first original series, OITNB paved the way for better visibility for transgender women of colour and ethnic minorities, while challenging heteronormativity on mainstream TV.

And now, Queer Eye – a 1990s feel-good makeover show which recently received a reboot on Netflix – has been lauded as a celebration of queerness.

To read more into the modern surge of queer storytelling, click here.

And Alan Cumming is soon to play the first ever openly gay lead in an American broadcast drama.

But it’s no secret that the on-screen representation LGBT+ issues and people is still lacking.

In recent years film critics have introduced the term “straightwashing” to highlight the marginalisation of the LGBT+ community in Hollywood, television, literature and in history.

Some critics accused the producers of the 2015 film Stonewall of ciswashing and whitewashing

What is straightwashing?

Straightwashing is the assimilation of someone who is gay, lesbian, bisexual asexual or other to fit heterosexual cultural norms. Put simply, it’s the practice of portraying non-straight people or characters as straight.

The practice of straightwashing marginalises the LGBT+ community by erasing queer people – who are already underrepresented.

But more than that, staightwashing also perpetuates the idea that films or shows need to be made “straight” to appeal to a wider audience, which is rooted in homophobia.

LGBT+ representation on-screen is improving but there is still work to be done

Ciswashing, which is the practice of portraying someone who is non-binary as cisgendered, is also a problem.

The issue with straightwashing (and ciswashing) is that it has the ability to undermine the progress of the LGBT+ movement in wider society by obscuring stories of the LGBT+ community.

Showing LGBT+ lives, experiences, relationships and friendships normalises LGBT+ people, which is a step toward eliminating discrimination.

Examples of straightwashing

Despite this, LGBT+ characters continue to face obstacles on-screen and in print – particularly in adaptations of comic books.

The X-Men character Mystique, for example, is bisexual in the comic books but has been portrayed as straight in the films the character has appeared in.

The 2018 superhero film Black Panther, marked as a groundbreaking celebration of diversity for it’s predominantly black cast, was recently criticised for allegedly removing a lesbian romance from the film.

After the film was announced, the characters Okoye and Ayo were expected to get together as they do in the comic book.

When the erasure was questioned by fans, a Marvel spokesperson replied: “The nature of the relationship between Danai Gurira’s Okoye and Florence Kasumba’s Ayo in Black Panther is not a romantic one.”

Earlier this year, Harry Potter fans accused the makers of Fantastic Beasts and Where To Find Them of straightwashing the sequel, when director David Yates said the character of Dumbledore will not be explored in the film.

Back in 2007, JK Rowling proclaimed the Hogwarts headmaster Albus Dumbledore was gay.

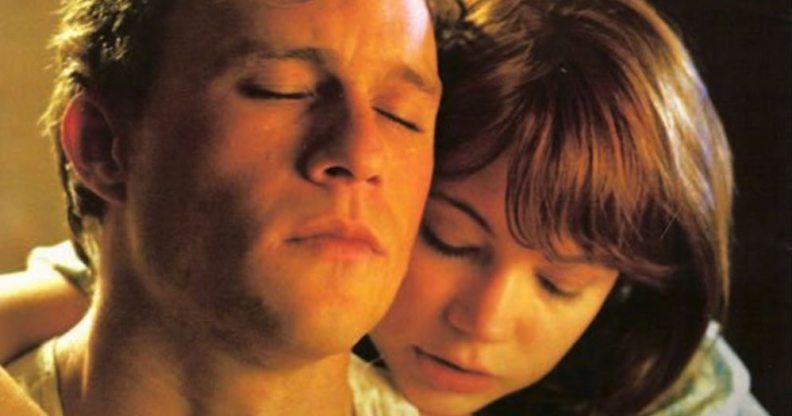

OITNB has helped challenge heteronormativity on TV

It’s not just a recent phenomenon, too – straightwashing has been a problem throughout the history of cinema.

The 1946 biopic Night and Day, which told the story of American composer Cole Porter, who was gay, removed any reference to homosexuality in the film.

Even films which centre on the stories of LGBT+ lives can’t escape the problem.

The 2015 film Stonewall, based on the riots where LGBT+ people protested a police raid at the Stonewall Inn, was criticised for ciswashing and whitewashing for erasing the black trans activists Marsha P Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, who led the riots.

Critics pointed out that by removing Johnson and Rivera, the producers were diminishing the accomplishments of transgender people and rewriting history.

What else does straightwashing impact?

It’s not just films or TV programmes themselves that are affected by straightwashing, ciswashing or whitewashing – or a combination of them all – but posters and DVD covers too.

Last year, critics accused Sony UK of straightwashing a poster for the film Call Me By Your Name, the story of a teenage boy who has a sexual relationship with an older man.

One promotional poster showed the boy with a female friend he has a doomed relationship with, rather than the gay romance – which critics argued incorrectly presented the film as heterosexual.

The film Pride, which told the story of a group of London-based gay and lesbian activists who stood up for striking Welsh coal miners in 1984, was criticised after the film’s distributors in the US removed references to homosexuality on the DVD cover.

The original synopsis for Pride references the “London-based group of gay and lesbian activists” that supported the miners, but the US packaging mentions only “London-based activists” in its version, PinkNews reported at the time.

Stepping away from popular culture, straightwashing can impact incidents too – such as the 2016 shooting at the LGBT+ nightclub Pulse in Orlando, which killed 49 people and wounded dozens of others.

In the aftermath of the shooting, activists highlighted how the attack was straightwashed by some politicians who appeared to avoid using the word gay – or any LGBT terminology – to describe the atrocity.

The Republican National Committee, for example, issued a statement condemning “violence against any group of people simply for their lifestyle or orientation”.

Activists argued denying the nature of the attack as a hate crime against LGBT+ people would only perpetuate violence, discrimination and abuse.